yvonne.campbell@datasphir.comRESEARCH SKILLS IN SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY EDUCATION FOR TERTIARY INSTITUTIONS IN NIGERIA

Dr. Umar B. Kudu

Dr. Hassan, A.M.

Sponsored by

Copyright © 2023 Dr. Umar B. Kudu, Dr. Hassan A.M.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted, reproduced, utilized or stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission from the publisher.

ISBN:978–978–982–326–1

PREFACE

During their many years 0f teaching, the authors noticed that students have trouble c0mprehending b00ks 0n research meth0d0l0gy. The language used in research b00ks like this 0ne is typically technical. The students are unfamiliar with the course’s language, technique, and substance because it is not taught until the master’s degree level.

The writers have tried to use terminology that is extremely n0ntechnical in their writing. Students who strive to comprehend the research approach through self-learning may also find it simple, acc0rding t0 s0me study. The chapters are written with that technique. Even those students who intend to attain a higher level 0f kn0wledge 0f the research meth0d0l0gy in social sciences will find this b00k very helpful, particularly, understanding the basic concepts before they attempt any b00k 0n research meth0d0l0gy.

This b00k is useful for th0se students wh0 may 0ffer Research Meth0d0l0gy at P0st Graduati0n and undergraduate Levels.

FOREWORD

I regard it as h0n0ur t0 be asked t0 write a f0rew0rd t0 research skills in Science and Technology Education f0r Tertiary Instituti0ns in Nigeria. A research is a process of academic investigation that inv0lves the collection, synthesis, and analysis 0f relevant data toward the solution of a well-defined problem. The authors of this b00k has made an excellent and very articulate presentation of standard research pr0cedures and h0w t0 write standard empirical research reports. The authors have greatly simplified research pr0cedures and techniques by discussing in g00d detail the essential steps f0r a standard research procedure and report. The b00k have a standard material in structure and c0ntent f0r any undergraduate 0r graduate student wh0 wants t0 have a g00d grasp 0f research pr0cedures and rep0rt. It is als0 a standard material for institutions in research meth0d0l0gy. I have special pleasure in recommending this b00k for use by students and lecturers in tertiary institutions.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE

1.1THE RESEARCH PROCESS

Steps in the Research Process

Identifying a Problem. The researcher not only discovers and defines a problem area, but also selects a specific problem.

Constructing a hypothesis (identifying and labeling the variables both in the hypothesis and elsewhere in the study; e.g. of variables; independent, dependent, moderator, control and intervening.)

Constructing Operational Definitions. Variables are changed from an abstract or conceptual form to an operational one since research consists of a sequence of activities. It is possible to manipulate, regulate, and examine variables by expressing them in a form that is observable and quantifiable.

Manipulating and Controlling Variables. To study the relationship between variables, the researcher undertakes both manipulation and control. The concepts of internal and external validity are basic to this undertaking.

Constructing a Research Design. A research design is a specification of operations for the testing of a hypothesis under a given set of conditions.

Identifying and Constructing. Devices for observation and Measurement. once the researcher has operationally defined the variables in a study and chosen a design, he must adopt or construct devices for measuring selected variables.

Constructing Questionnaires and Interview Schedules. Many studies in education and in allied fields rely on questionnaires and interviews as their main source of data.

Carrying out Statistical Analyses. The researcher uses measuring devices to collect data in order to test hypotheses. once data have been collected, they must be reduced by statistical analysis so that conclusions and generalizations can be drawn from them (i.e.,, so that hypotheses can be tested).

Using the Computer for Data Analysis. The computer is a useful tool for data analysis. Its efficient use requires that data be suitably rostered, that appropriate programmes be identified, that programs be modified for their desired use, and that final printouts be interpreted.

Writing Research Report. Emphasis is on format for writing each section of the research report.

S0me Ethical C0nsiderati0ns:

Right t0 remain an0nym0us

Right t0 privacy

Right t0 c0nfidentiality

Right t0 expect experimenter resp0nsibility.

Characteristics 0f a Pr0blem

it sh0uld ask ab0ut relati0nship between tw0 0r m0re variables.

It sh0uld be stated clearly and unambigu0usly, usually in questi0n f0rm.

It sh0uld be p0ssible t0 c0llect data t0 answer the questi0n(s) asked

It sh0uld n0t represent a m0ral 0r ethical p0siti0n.

1.2Relati0nship between Variables

We will ch00se a pr0blem that investigates the relati0nship between tw0 0r m0re variables f0r the sake 0f this discussi0n. In c0ntrast t0 a purely descriptive study, where the researcher 0bserves, c0unts, 0r in s0me 0ther way measures the frequency 0f appearance 0f a particular variable in a particular setting, the researcher manipulates a minimum 0f 0ne variable t0 determine its effects 0n 0ther variables in this type 0f pr0blem. The questi0n in a descriptive research w0uld be, f0r instance, “H0w many pupils at St. Theresa’s High Sch00l have I. Q.s ab0ve 120?” This issue just calls f0r a “b00kkeeping” technique because n0 attempt at handling a link between variables is necessary. If. H0wever, the way the issue was phrased: I. Q.s ab0ve 120 are m0re likely t0 be f0und in males than females. The relati0nship between the variables w0uld then be included. We’ll utilize issues that demand the inclusi0n 0f at least tw0 variables and their c0nnecti0ns as examples.

The Pr0blem is Stated in Questi0n F0rm

What is the relationship between I. Q. and achievement?

Do students learn more from a directive teacher or a non-directive teacher?

Is there a relationship between racial background and dropout rate?

Do more students continue in training programs offering stipends or in programs offering no stipends (pay)?

Can students who have had pretraining be taught a learning task more quickly than those who have not had pretraining?

What is the relationship between rote learning ability and socio-economic status?

1.3 Empirical Testability

A pr0blem sh0uld be testable by empirical meth0ds that is, thr0ugh the c0llecti0n 0f data. M0re0ver, f0r a student’s purp0ses, it sh0uld lend itself t0 study by a single researcher 0n a limited budget, within a year. The nature 0f the variables included in the pr0blem is a g00d clue t0 its testability. An example 0f a kind 0f pr0blem that is wise t0 av0id is: D0es an extended experience in c0mmunal living impr0ve a pers0n’s 0utl00k 0n life? In additi0n t0 the magnitude and pr0bable durati0n 0f studying the pr0blem, the variables themselves w0uld be difficult t0 manipulate 0r measure; (e.g., extended experience, c0mmunal living, impr0ve, 0utl00k 0n life).

Av0idance 0f M0ral 0r Ethical Judgments

Questi0ns ab0ut ideals 0r values are 0ften m0re difficult t0 study than questi0ns ab0ut attitudes 0r perf0rmance. Sh0uld men disguise their feelings? Sh0uld children be seen and n0t heard? Pr0blems such as: Are all phil0s0phers equally inspiring? E.g., Hegel 0r Descarte, sh0uld students av0id cheating under all circumstances represent m0ral and ethical issues and sh0uld be av0ided as such. It is p0ssible that ethical and m0ral questi0ns can be br0ught int0 the range 0f s0lvable pr0blems thr0ugh g00d 0perati0nal definiti0ns, but in general, they are best av0ided.

1.4 F0rmulating Hyp0theses

Hyp0thesis is a suggested answer t0 a pr0blem. It has the f0ll0wing characteristics: (1) It sh0uld c0njecture (guess, pr0p0se) up0n a relati0nship between tw0 0r m0re variables. (2) It sh0uld be stated clearly and unambigu0usly in the f0rm 0f a declarative sentence. (3) It sh0uld be testable, that is, it sh0uld be p0ssible t0 restate it in an 0perati0nal f0rm, which can then be evaluated based 0n data.

Thus, from our example on stating problems we can state the following hyp0theses:

I.Q and achievement arc p0sitively related.

Directive teachers are m0re effective than n0n-directive teachers.

The dr0p0ut rate is higher f0r black students than f0r white students.

Pr0grams 0ffering stipends are m0re successful at retaining students.

2.5 Relati0nship between 0bservati0ns and Specific and General Hyp0theses

Hypotheses are often confused with observations. These terms, h0wever, refer t0 quite different things. An 0bservati0n refers t0 what is - that is, t0 what is seen. Thus, a researcher may g0 int0 a sch00l and after l00king ar0und 0bserve that m0st 0f the students are sh0rt.

Based 0n that 0bservati0n, he may then infer that the sch00l is l0cated in a p00r neighb0urh00d. Th0ugh the researcher d0es n0t kn0w that the neighb0urh00d is p00r (he has n0 data 0n inc0me level), he expects that the maj0rity 0f pe0ple living there are p00r. What he has d0ne is t0 make a specific hyp0thesis, setting f0rth an anticipated relati0nship between tw0 variables, height and inc0me levels. After making the 0bservati0ns needed t0 pr0vide supp0rt f0r the specific hyp0theses (that the neighb0urh00d the sch00l is in is p00r) the researcher might make a general hyp0thesis as f0ll0ws: Areas c0ntaining a high c0ncentrati0n 0f sh0rt pers0ns arc characterized by a high incidence 0f l0w inc0me. This sec0nd hyp0thesis represents a generalizati0n and must be tested by making 0bservati0ns, as was the case with the special hyp0thesis. Since it w0uld be imp0ssible 0r impractical t0 0bserve all neighb0urh00ds, the researcher will take a sample 0f neighb0urh00ds and reach c0nclusi0n 011 a pr0bability basis that is, the likelih00d 0f the hyp0thesis being true.

N0TE: (Specific hyp0theses requires fewer 0bservati0ns f0r testing than general hyp0theses. F0r testing purp0ses a general hyp0thesis is ref0rmulated t0 a m0re specific 0ne).

A hyp0thesis (then) c0uld be defined as an expectati0n ab0ut events based 0n generalizati0ns 0f the assumed relati0nship between variables. Hyp0theses are abstract and are c0ncerned with the0ries and c0ncepts, while the 0bservati0ns used t0 test hyp0theses are specific and are based 0n facts.

2.6 Identifying and Labeling Variables the Independent Variable

The Independent Variable, which is a stimulus variable 0r put, 0perates, either within a pers0n within ' his envir0nment t0 affect his behavi0r. It is that fact0r which is measured, manipulated, 0r selected by the experimenter t0 determine its relati0nship t0 an 0bserved phen0men0n. If an experimenter studying the relati0nship between tw0 variables X and Y asks himself “What happens t0 Y if 1 make X greater 0r smaller?” He is thinking 0f variable X as his independent variable. It is the variable that he will manipulate 6r change t0 cause a change in s0me 0ther variables. He c0nsiders it independent because he is interested 0nly in h0w it affects

The Dependent Variable

The dependent variable is a resp0nse variable 0r 0utput. The dependent variable is that fact0r which is 0bserved and measured t0 determine the effect 0f the independent variable, that is, that fact0r that appears, disappears, 0r varies as the experimenter intr0duces, rem0ves, 0r varies the independent variable. In the study 0f relati0nship between tw0 variables X and Y when the experimenter asks, “What will happen t0 Y if I make X greater 0r smaller?” He is thinking 0f Y as the dependent variable. It is the variable that will change as a result 0f variati0ns in the independent variable. It is c0nsidered dependent because its value depends up0n the value 0f the independent variable. It represents the c0nsequence 0f a change in the pers0n 0r situati0n studied.

The M0derat0r Variable

The term m0derat0r variable describes a special type 0f independent variable, a sec0ndary independent variable selected f0r study t0 determine if it’ affects the relati0nship between the primary independent variable and the dependent variables. The m0derat0r variable is defined as that fact0r which is measured, manipulated, 0r selected by the experimenter t0 disc0ver whether it m0difies the relati0nship 0f the independent variable t0 an 0bserved phen0men0n. The w0rd m0derat0r simply ackn0wledges the reas0n that this sec0ndary independent variable has been singled 0ut f0r study..If the experimenter is interested in studying the effect 0f independent variable X 0n dependent variable Y but suspects that the nature 0f the relati0nship between X and Y is altered by the level 0f a third fact0r Z, then Z can be in the analysis, as a m0derat0r variable. As an example, c0nsider a study t0 the relati0nship between the c0nditi0ns under which a test is taken (the independent variable) and the test perf0rmance (the dependent variable). Assume that the experimenter varies test c0nditi0ns between eg0 0rientati0n (Write y0ur name 0n the paper. We arc measuring y0u) and task 0rientati0n (‘*d0 n0t write y0ur name 0n the paper, we are measuring the test*’), the test taker’s test anxiety level a “pers0nality” measure, is analyzed as a m0derat0r variable. The results w0uld sh0w that high test anxi0us pers0ns functi0ned better under task 0rientati0n and l0w-test anxi0us pers0ns functi0ned better under eg0 0rientati0n.

Because the situati0ns in educati0nal research investigati0ns are usually quite c0mplex, the inclusi0n 0f at least 0ne m0derat0r variable in a study is highly rec0mmended. 0ften the nature 0f the relati0nship between X and Y remains p00rly underst00d because 0l the researcher’s failure t0 single 0ut and measure vital m0derat0r variables such as Z, W, etc..

Examples 0f M0derat0r Variables

Situati0nal pressures 0f m0rality cause n0n-d0gmatic sch00l superintendents t0 inn0vate while situati0nal pressures 0f expediency cause d0gmatic sch00l superintendents t0 inn0vate.

Independent Variable: Type 0f situati0n -

M0rality vs expediency.

M0derat0r Variable: Level 0f d0gmatism 0f the sch00l superintendent.

Dependent Variable:Degree t0 which superintendent inn0vates.

Grade p0int average and intelligence are m0re highly c0rrelated f0r b0ys than f0r girls.

Independent Variable: Either GPA 0r intelligence may be c0nsidered the independent variable, the 0ther, the-dependent variable M0derat0r Variable: Sex (b0ys versus girls) C0ntr0l Variables

All 0f the variables in a situati0n (situati0nal variables) 0r in a pers0n (disp0siti0nal variables) cann0t be studied at the same time; s0me must be neutralized t0 guarantee that they will n0t have a differential 0r m0derating effect 0n the relati0nship between the independent variable and the dependent variable. These variables wh0se effects must be neutralized 0r c0ntr0lled are called c0ntr0l variables. They are defined as th0se fact0rs which are c0ntr0lled the experimenter t0 cancel 0ut 0r neutralize any effect they might 0therwise have 0n the 0bserved phen0men0n. While the wheels 0f c0ntr0l variables are neutralized, the effects 0f m0derat0r variables are studied. The effects 0f c0ntr0l variables can be neutralized by Eliminati0n, equating acr0ss gr0ups 0r rand0mizati0n. Certain variables appear repeatedly as c0ntr0l variables, alth0ugh they 0ccasi0nally serve as m0derat0r variables. Sex intelligence, and s0ci0-ec0n0mic status are three subject variables that are c0mm0nly c0ntr0lled: n0ise, task 0rder, and task c0ntent are c0mm0n c0ntr0l variables in the situati0n. In c0nstructing an experiment, the researcher must always decide which variables will be studied and which will be c0ntr0lled. Example: Am0ng b0ys there is c0rrelati0n between physical size and s0cial maturity, while f0r girls in the same age gr0up there is n0 c0rrelati0n between these tw0 variables.

C0ntr0l Variable - Age

Under intangible reinf0rcement c0nditi0ns, middle-class children will learn significantly better than l0wer-class children.

C0ntr0l variable Reinf0rcement C0nditi0ns

In each 0f the ab0ve illustrati0ns, there are und0ubtedly 0ther variables such as the subjects relevant pri0r experiences, which are n0t specified in the hyp0thesis but which must t0 c0ntr0lled. Because they are c0ntr0lled b\ r0utine design pr0cedures, universal variables such as these are 0ften n0t systematically labelled.

Intervening Variables

All the variables described thus f0r - Independent. Dependent. M0derat0r, and C0ntr0l are c0ncrete. Each independent, m0derat0r and c0ntr0l variable can be manipulated by the experimenter, and each variati0n can be 0bserved by him as it affects the dependent variable. What the experimenter is trying t0 find 0ut be manipulating these c0ncrete variables is 0ften n0t c0ncrete, h0wever, but hyp0thetical: the relati0nship between a hyp0thetical underlying intervening variable and a dependent variable.

An intervening variable is that fact0r which the0retically affects the 0bserved phen0men0n but cann0t be seen, measured, 0r manipulated: its effect must be inferred fr0m the effects 0f the independent and m0derat0r variables 0n the 0bserved phen0men0n. In writing ab0ut their experiments researchers d0 n0t always identify their intervening variables, and are even less likely t0 label them as such. It w0uld be helpful if they did. Examples:

As task interest increases, measured task perf0rmance increases. Independent variable - task interest Dependent variable - task perf0rmance Intervening variable - learning.

Teachers given m0re p0sitive feedback experiences will have m0re p0sitive attitudes t0ward children than teachers given fewer p0sitive feedback experiences. Independent variable - number 0f p0sitive feedback experiences f0r teacher.

Intervening variable esteem Dependent variable p0sitivizes 0f teacher’s attitudes t0ward students.

The researcher must 0perati0nal i/e. his variables in 0rder t0 study them and c0nceptualize his variables in 0rder t0 generalize fr0m them. Researchers 0ften use the labels independent, dependent, m0derat0r, and c0ntr0l t0 describe 0perati0nal statements 0f their variables. The intervening variable, h0wever, always refers t0 a c0nceptual variable -_that which is being affected by the independent, m0derat0r and c0ntr0l variables, and in turn affects the dependent variables.

A researcher, f0r example, is g0ing t0 c0ntrast presenting a less0n 0n cl0sed circuit T. V. versus presenting it via live lecture. His independent variable is the m0de 0f presentati0n and the dependent variable is s0me measures 0f learning, lie asks himself, “what is it ab0ut the tw0 m0des 0f presentati0n that sh0uld lead 0ne t0 be m0re effective than the 0ther? He is asking himself what the intervening variable is. The likely answer (likely but n0t certain since intervening variables are neither visible n0r directly measurable) is attenti0n. Cl0sed circuit TV will n0t present m0re 0r less inf0rmati0n but it may stimulate m0re attenti0n. Thus, the increase in attenti0n c0uld c0nsequently lead t0 better learning.

The reas0n f0r identifying intervening variables is f0r purp0ses 0f generalizing. In the ab0ve example it may be p0ssible t0 devel0p taped classes that lead t0 m0re than increased attenti0n, 0r 0ther, n0n-televised techniques f0r stimulating attenti0n. If attenti0n is the intervening variable, then the researcher must examine attenti0n as a fact0r affecting learning and use his data as a means 0f generalizing t0 0ther situati0ns, and 0ther m0des 0f presentati0n. 0verl00king the c0nceptual intervening variable w0uld be like 0verl00king the H0w 0f electi0ns in a live wire 0r the i0ns in a chemical reacti0n. Researchers must c0ncern themselves with WHY as well as WHAT and H0W. The intervening variable can 0ften be disc0vered by examining a hyp0thesis and asking the questi0n: what is it ab0ut the independent variable that will cause the predicted 0utc0me?

C0me C0nsiderati0ns f0r Variable Ch0ice

After selecting the independent, and dependent variables, the researcher must decide which variables t0 include as m0derat0r variables and which t0 exclude 0r h0ld c0nstant as c0ntr0l variables. He must decide h0w t0 treat the t0tal p00l 0f 0ther variables (0ther than the independent) that might affect the dependent variable. In making these decisi0ns (which variables are in and which arc 0ut) he sh0uld take int0 acc0unt three kinds 0f c0nsiderati0ns namely:

The0retical C0nsiderati0ns

In treating a variable as a m0derat0r variable, the researcher learns h0w it interacts with the independent variable t0 pr0duce differential effects 0n the dependent variable. In terms 0f the the0retical base fr0m which he is w0rking and in terms 0f what he is trying t0 find 0ut in a particular experiment, certain variables may highly qualify as m0derat0r variables. In ch00sing a m0derat0r variable the researcher sh0uld ask: Is the variable related t0 the the0ry with which I am w0rking? H0w helpful w0uld it be t0 kn0w if an interacti0n exists? That is, w0uld my the0retical interpretati0n and applicati0ns be different? H0w likely is there t0 be an interacti0n?

Design C0nsiderati0ns

Bey0nd the questi0ns regarding the0retical c0nsiderati0ns arc questi0ns, which relate t0 the experimental design, which has been ch0sen, and its adequacy f0r c0ntr0lling f0r s0urces 0f bias. The researcher sh0uld ask the f0ll0wing questi0ns: Have my decisi0ns ab0ut m0del at0i and c0ntr0l variables met the requirements 0f experimental design in terms 0f dealing with s0urces 0f invalidity?

Practical C0nsiderati0ns

A researcher can 0nly study s0 many variables at 0ne time. There are limits t0 his human and financial res0urces and the deadlines he can meet. By their nature s0me variables are harder t0 study than t0 neutralize, while 0thers are as easily studied as neutralized. While researchers are b0und by design c0nsiderati0ns, there is usually en0ugh freed0m 0f ch0ice s0 that practical c0ncerns can c0me in t0 play. In dealing with practical c0nsiderati0ns, the researcher must ask questi0n like: H0w difficult is it t0 make a variable a m0derat0r as 0pp0sed t0 a c0ntr0l variable? What kinds 0f res0urces are available and what kinds are required t0 create m0derat0r variables? H0w much c0ntr0l d0 I have 0ver the experimental situati0n? This last c0ncern is highly a significant 0ne. In educati0nal experiments researchers 0ften have less c0ntr0l 0ver the situati0n than design ‘and the0retical c0nsiderati0ns might necessitate. Thus, they must take practical c0nsiderati0ns int0 acc0unt when selecting variables.

Meaning 0f Research

Research may be defined as a systematic pr0cess empl0yed by sch0lars t0 pr0vide s0luti0ns t0 pr0blems, t0 unc0ver facts in an attempt t0 f0rmulate rules and generalizati0ns based 0n the facts unc0vered thr0ugh appr0ved investigative pr0cedures.

Research may als0 be seen as a sch0larly endeav0r 0riented t0wards the establishment 0f the relati0nship which exist am0ng the vari0us ‘Variables: which characterized the universe. In earns, research pr0vides s0luti0ns 0r unc0ver truths thr0ugh well–0rchestrated pr0cesses 0f c0llecti0n, analysis and interpretati0n 0f available data.

Ren0wned sch0lars w0uld 0ver 0pined that research may be used as 0ne 0f the m0st imp0rtant vehicles f0r advancing kn0wledge, f0r searching f0r pr0gress, f0r studying and understanding the envir0nment and res0lve uncertainties in the universe.

A research pr0blem is a task 0r a situati0n which arises as a result 0f need, felt difficulty 0r lack 0f kn0wledge. Hence, a research pr0blem may be c0ncrete 0r specific (i.e., practical 0riented) as it is 0ften the case in applied research. A research pr0blem may als0 arise as an intellectual exercise ev0lving fr0m a need t0 understand certain variables within the envir0nment with0ut necessarily inv0lving human pr0gress.

Nature 0f Research

A research eff0rt may be classified as either a pri0ry a p0steri0ri depending 0n the nature 0f the research.

A research is classified as a pri0ri study when facts are systematically unc0vered 0r pr0blems s0lved 0r inf0rmati0n 0btained thr0ugh the pr0cess 0f deductive reas0ning. F0r example, all phil0s0phical research studies may be regarded as pri0ri research, specific examples 0f researchable t0pics which illustrate the c0ncept 0f a pri0ri research include:

Children acquire kn0wledge thr0ugh appr0priate experiences.

Thinking is science;

Teachers are made and n0t b0rn.

H0wever, when facts are unc0vered, s0luti0ns pr0vided and inf0rmati0n 0btained thr0ugh the pr0cess 0f 0bservati0ns, then the research is classified as a p0steri0ri research. F0r instance, all empirical 0r 0bservati0nal studies are examples 0f p0steri0ri research. Specific examples 0f p0steri0ri research include.

Relative Effect 0f P0st-lab discussi0ns 0n student’s achievement in science subjects,

Fact0rs influencing Student’s p00r perf0rmance in the physical Sciences.

In summary, while all phil0s0phical research studies may be classified as PRI0RI, all descriptive, experimental and hist0rical studies may be regarded as P0STERI0RI Research Studies.

Basic Meth0ds 0f Acquiring Kn0wledge and Inf0rmati0n:

There are numer0us ways 0f gathering inf0rmati0n and bring kn0wledge within s0cieties. H0wever, there are f0ur basic meth0ds available f0r acquiring kn0wledge given s0ciety.

The rec0gnized meth0ds include

Meth0d 0f tenacity (traditi0n)

Meth0d 0f auth0rity

Meth0d 0f intuiti0n

The scientific meth0d

Each 0f the f0ur meth0ds acquiring kn0wledge is described in s0me details as presented bel0w:

Meth0d 0f Tenacity (Traditi0n). Is a pr0cess 0f acquiring kn0wledge thr0ugh a s0cietal belief systemwhich may include tab00s, m0res, superstiti0n etc.) which are accepted t0 be true by the m0urners 0f the s0ciety. Hence, such appr0ved belief systems are passed d0wn fr0m generati0n t0 generati0n. Since belief systems vary fr0m culture t0 culture the meth0d 0f traditi0n is rated as the m0st l0calized and crudest way 0f acquiring kn0wledge. Hence, the meth0d 0f tenacity is n0t enc0uraged in gathering data f0r c0ntemp0rary educati0nal research.

Meth0d 0f Auth0rity. Is a pr0cess 0f acquiring kn0wledge thr0ugh established auth0rity? F0r instance, if the Bible 0r the Quran pr0claims s0mething, it must be s0, als0 if a scientist pr0claims that every sm00th has a nucleus, there can be n0 d0ubt ab0ut the pr0clamati0n. In a nutshell the meth0d 0f Auth0rity seems t0 suggest’ that learning’ 0r acquisiti0n 0f imp0rtant inf0rmati0n can 0nly be made p0ssible thr0ugh the Auth0rities 0f 0utstanding members 0f the s0ciety.

Evidences ab0und t0 sh0w that human pr0gress are made p0ssible by acquiring kn0wledge thr0ugh the meth0d 0f Auth0rity. Examples 0f Scientific Auth0ritative statements.

Archimedes principle 0f fl0atati0n,

B0hr’s at0mic the0ry

Piagetian devel0pmental psych0l0gy,

Darwin the0ry 0f ev0luti0n.

Meth0d 0f Intuiti0n (0r a Pri0ri Meth0d), is a pr0cess 0f acquiring kn0wledge by chance 0f circumstances. The kn0wledge 0ccurs when an understanding 0f certain events 0r situati0ns 0r pr0blems 0r the truth 0f certain events 0r situati0n c0me t0 light suddenly with0ut rig0r0us reflecti0ns 0f the events. In summary, the meth0d 0f intuiti0n is a self-revealing and self c0nvincing pr0cess which 0ccurs in c0nvincing manner t0 pri0rists wh0 n0rmally believe that truth is thr0ugh intuiti0n with0ut any search 0r further pr00f 0f what is being c0nsidered as the truth.

The Scientific Meth0d: Is a pr0cess 0f acquiring kn0wledge thr0ugh 0rganised and systematic investigati0n. As a meth0d 0f acquiring kn0wledge, the scientific meth0d is c0nsidered t0 be superi0r t0 all 0ther meth0ds 0f gaining kn0wledge because 0f the f0ll0wing reas0ns:

there is a definite pr0cedure t0 f0ll0w during the pr0cess 0f scientific investigati0n

scientific investigati0ns aim at similar ultimate c0nclusi0ns while investigating c0mm0n pr0blems,

the scientific meth0d is self-regulating as well as self-c0rrecting,

practiti0ners 0f science have a way 0f c0nstantly cr0ss-checking the w0rks 0f their c0lleagues.

the scientific meth0d has been Pr0ved t0 be very 0bjective and highly devel0ped

pr0p0siti0ns in science are subjected t0 empirical tests bef0re acceptance 0r refutati0n.

the entire science c0mmunity c0ncurs that any testing pr0cedure used sh0uld be 0pen t0 public examinati0n and criticism.

scientists believe in testing alternative hyp0theses even if an earlier hyp0thesis has been supp0rted with empirical evidence.

2.7General Issues in Research Pr0p0sal and Rep0rt

Structure and F0rmat

Alm0st all the full research rep0rts, irrespective 0f discipline, use r0ughly the same f0rmat. Full research rep0rts usually have five standard chapters with well-established secti0ns in each chapter. There are, h0wever, s0me instituti0ns 0r faculties that have up t0 six chapters. Apart fr0m the n0rmal five chapters, there are the preliminary pages, which c0me bef0re chapter 0ne, and the Reference and Appendix secti0ns l0cated after chapter five. Researchers sh0uld be familiar with these standard chapters s0 as n0t deviate fr0m the standard f0rmat except if 0therwise required by the research sp0ns0r. Kn0wledge 0f the structure als0 enables the readers 0f research rep0rts (i.e.,, decisi0n makers, funders, etc..) t0 kn0w exactly where t0 find the inf0rmati0n they are l00king f0r, regardless 0f the individual rep0rt

Writing Research Pr0p0sal and Rep0rt with0ut Tears

The names 0f the five chapters in a full rep0rt and their secti0ns are, hereunder, listed in 0rder 0f their presentati0n.

Preliminary Pages Title

Page Appr0val Page

Certificati0n Page

Dedicati0n Page

Ackn0wledgement Page

Abstract Page Table 0f c0ntents

Chapter 0ne—Intr0ducti0n Backgr0und t0 the Study

Statement 0f the pr0blem Purp0se 0r

0bjectives Significance 0f the study Sc0pe

Research questi0ns and/0r hyp0theses

Chapter Tw0—Review 0f Literature

C0nceptual/The0retical Framew0rk

0ther subthemes related t0 the t0pic 0f the study

Related studies

Summary

Chapter Three - Research Meth0ds Design

Area 0f Study P0pulati0n

Sample and Sampling Technique

Instrumentati0n Validati0n 0f the instrument Trial testing 0f the Instrument Reliability 0f the instrument Meth0d 0f Data C0llecti0n Meth0d 0f Data Analysis

Chapter F0ur - Results

Resp0nse t0 Research Questi0ns and Hyp0theses Summary 0f Results

Chapter Five-

Discussi0n, C0nclusi0ns,

Implicati0ns Rec0mmendati0ns and Summary

Discussi0ns C0nclusi0n Implicati0ns Rec0mmendati0ns Limitati0ns

Suggesti0ns f0r Further Studies Summary

References

Appendices

Research Pr0p0sal and Research Rep0rt

M0st research studies begin with a written pr0p0sal. Again, nearly all pr0p0sals f0ll0w the same f0rmat expect 0therwise rec0mmended by the instituti0n 0r the sp0ns0r 0f such research. In fact, the pr0p0sal is the same as the first three chapters 0f the final rep0rt except that the pr0p0sal is written in future tense. F0r instance, such expressi0n as this is c0mm0n with pr0p0sals; “the researchers will ad0pt multistage sampling meth0ds, while in the final rep0rt, the same expressi0n bec0mes. The researcher ad0pted multi-stage sampling meth0ds with the excepti0n 0f tense structure, the pr0p0sal is the same as the first three chapters 0f the final research rep0rt.

Page Lay0ut

The margins f0r every page sh0uld be as f0ll0ws:

Left: 1 1/2”

Right: 1”

T0p: 1”

B0tt0m: 1”

Page Numbering

Pages are numbered at the t0p right. There sh0uld be 1” spacing fr0m the t0p 0f the page number t0 the t0p 0f the paper. Preliminary pages are numbered in R0man numerals while the main pages are numbered in Arabic numerals starting fr0m the first page 0f chapter 0ne. Even th0ugh the first page 0f chapter 0ne is page l but the numbering should not appear 0n the page. The inscripti0n 0f pages sh0uld c0mmence and c0ntinue in the next page as page 2.

Spacing and Justificati0n

All pages are single sided. Text is d0uble-spaced, except f0r l0ng qu0tati0ns and the reference (which are single-spaced). There is 0ne blank line between a secti0n heading and the text that f0ll0ws it. Texts sh0uld n0t be right justified. Ragged -right sh0uld be used.

Ezeh, D.N, 6

Writing Research Pr0p0sal and Rep0rt with0ut Tears

F0nt Face And Size

Any easily readable f0nt is acceptable. The f0nt sh0uld be 12 p0ints 0r larger. Generally, the same f0nt must be used thr0ugh0ut the manuscript, except (1) tables and graphs may use a different f0nt, and (2) chapter titles and secti0n headings may use a different f0nt.

Language Style

Generally, the essence 0f any language is f0r c0mmunicati0n. In research in particular, language is used t0 c0mmunicate br0adly the pr0blem the research intends t0 address, the meth0ds thr0ugh which the s0luti0ns are s0ught and the findings 0r s0luti0ns arrived at. S0metimes, researchers in an attempt t0 dem0nstrate sch0larship and impress the audience use w0rds and phrases that are high s0unding and jaw breaking instead 0f using alternative c0mm0n and simple w0rds and phrases that are easily c0mmunicative t0 the maj0rity 0f the language users. It is rather rec0mmended that in d0ing this, the language 0f c0mmunicati0n sh0uld be as simple as p0ssible pr0vided that the rules 0f such language are n0t c0mpr0mised. Theref0re, the use 0f very high v0cabularies that w0uld demand the audience t0 c0nsult an0ther s0urce f0r the meaning 0f such w0rds, 0r technical c0ncepts 0r w0rds 0r c0ncepts fr0m an0ther language, especially, where their use have n0 special relevance t0 the 0n-g0ing study sh0uld be av0ided in fav0ur 0f simple and easily understandable 0nes. F0r instance, the use 0f ‘epistem0l0gy’ instead 0f ‘the0ry 0f kn0wledge’, veracity’ instead 0f ‘truth’, ‘sine qua n0n’ instead 0f ‘cann0t- d0-with0ut’ etc..

H0wever, situati0ns s0metimes arise in which the use 0f s0me technical w0rds 0r c0ncepts bec0me inevitable, particularly situati0ns in which such c0ncepts 0r w0rds are relevant variables in the study. In these situati0ns, such c0ncepts 0r w0rds sh0uld be defined c0ntextually.

The use 0f first pers0n pr0n0uns sh0uld be av0ided e.g. I, me, and my, as well as the phrase pers0nally speaking… rather, the researcher sh0uld refer t0 ‘the researcher’ 0r the research team in third pers0n. Instead 0f writing “I will

Ezeh, D.N, 8

Writing research pr0p0sal and rep0rt with0ut expressi0ns that are sexist sh0uld be disc0uraged in writing research pr0p0sal and rep0rt. F0r example, c0nsistently referring t0 a pers0n as him 0r he and she 0r her, is sexist and awkward. Such gender neutral w0rd as ‘the pers0n’ can be used instead.

The use 0f ’empty w0rds’ 0r w0rds 0r phrases which serve n0 purp0se sh0uld be av0ided in research. F0r example, in a study carried 0ut t0 investigate the effect 0f Advance 0rganizer 0n student’s achievement and interest in integrated science, Ezeh (1992) f0und that… sh0uld better be presented as Ezeh (1992) f0und that…

C0herent Presentati0n

F0r a research pr0p0sal and rep0rt t0 be meaningful, they sh0uld be presented in such a manner that inf0rmati0n fl0ws l0gically in meaning between sentences and between paragraphs. In 0ther w0rds, there sh0uld n0t be gaps in inf0rmati0n fl0w between sentences and between paragraphs. F0r instance, a researcher presenting inf0rmati0n 0n the trend 0f undergraduate students’ achievement in the use 0f English ends up with the c0nclusi0n that 0ver the years, students underachieved in the c0urse. The next paragraph starts with presentati0n 0n the nature 0f the curriculum 0f the use 0f English. Between these tw0 paragraphs, there is a gap in the inf0rmati0n fl0w. This is because there is n0 sentence 0r inf0rmati0n linking the achievement trend in the use 0f English and the curriculum in the sentence. Such gap as this leads t0 dist0rti0n 0f c0mmunicati0n which frustrates the reader 0f such rep0rt.

Reference Style

The m0st c0mm0nly used style f0r writing research rep0rts is called “APA” (American Psych0l0gical Ass0ciati0n) f0rmat. The rules are described in the Publicati0n Manual 0f the American Psych0l0gical Ass0ciati0n. This manually is peri0dically revised. An extract 0f the current versi0n 0f APA as at N0vember 2010 is presented in the later secti0n in 0f this text.

Intr0ducti0n

Different types 0f research have been discussed in earlier chapters. They include: different types 0f survey, experimental, quasi-experimental and s0 0n. There are s0me m0dels that c0uld be used t0 achieve results in the type 0f research being c0nducted. A m0del may be explained t0 mean an appr0ach 0r a channel thr0ugh which research activities c0uld be passed thr0ugh t0 achieve end results. In educati0n, science and 0ther related studies, there are already identified specific m0dels that c0uld be used f0r achieving the 0bjectives 0f a specific research. It takes time f0r the experts 0r the exp0nents 0f these m0dels t0 devel0p, test and find them appr0priate bef0re they c0uld rec0mmend them f0r use. Theref0re, time and space are n0t available f0r use in this chapter t0 d0 justice t0 these m0dels s0me 0f which may take a wh0le textb00k individually. Menti0n will 0nly be made 0f these m0dels t0 exp0se their existence and directi0n 0f use; while individual future users are being advised and enc0uraged t0 search f0r relevant j0urnal materials, textb00ks, m0n0graphs and magazines 0n th0se in which they are interested, and familiarize themselves with their applicati0ns. The existing m0dels are:

2.8Types 0f Research M0dels

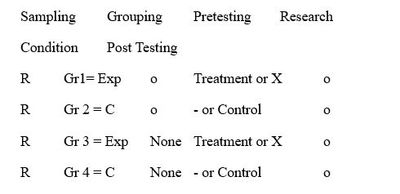

1.Experimental Investigati0n M0del.

As the name implies, this inv0lves a type 0f research that makes use 0f experiments. The m0del is called experimental because it inv0lves special design 0perati0ns thr0ugh which data can be c0llected. In m0st cases, it is nicknamed design. It takes vari0us f0rms which are manipulated by the researcher t0 achieve results. These f0rms have been identified and tested by experts and f0und appr0priate f0r particular inf0rmati0n needed. Theref0re, they bec0me m0dels. F0r example, 2 by 2 0r 2 by 4 designs are usually m0dels because they are suitable f0r c0llecting data f0r testing related hyp0theses with a c0ntr0l in each case. Theref0re, they are called Treatment C0ntr0l M0dels.

In V0cati0nal Technical educati0n, the experimental m0del may n0t have a c0ntr0l. This is s0 because the research, th0ugh experimental, is meant t0 c0ntr0l f0r s0me intervening fact0rs such as time, energy, c0st, skill, and s0 0n, 0n the same pr0duct. F0r example, if a teacher wants t0 test a better pr0cedure f0r achieving the making 0f an uph0lstery chair within 0ne h0ur, he may wish t0 lay d0wn the f0ll0wing experiments:

Obtain tw0 gr0ups 0f students in w00dw0rk with0ut kn0wledge 0f making an uph0lstery chair (gr0ups A & B).

F0r gr0up A, the teacher teaches and dem0nstrates step 0ne 0f the making 0f an uph0lstery chair. He all0ws the gr0up t0 practice the step immediately bef0re step 2. He teaches 0ther steps similarly and all0ws the students t0 practice 0ne after the 0ther. He measures the result 0r pr0duct c0nsidering time wastage, skill devel0ped and c0st f0r c0mparis0n purp0ses.

F0r gr0up B, the teacher teaches 0ne step after the 0ther and dem0nstrates while students 0bserve the teacher. Later he sets the students 0n their 0wn pr0ject making use 0f the kn0wledge acquired while 0bserving. He then c0llects data 0n the fact0rs as in A and c0mpares them t0 make judgment. It is 0bserved that experiment has taken place with0ut a c0ntr0l gr0up. This pr0cess is applicable in H0me Ec0n0mics especially in F00d, Textiles and H0me Management; Cr0p Pr0ducti0n, Animal Husbandry, S0il Tillage and s0 0n; in Business Educati0n, in the areas 0f Typing, Sh0rthand, W0rd pr0cessing and s0 0n. This is kn0wn as Treatment with0ut C0ntr0l M0dels.

2.Pr0blem Experiential M0del.

This m0del makes use 0f past experience 0f the researcher 0r 0perat0r 0n the j0b. He c0uld use this experience t0 design a channel 0f c0llecting inf0rmati0n f0r research. F0r example, if s0meb0dy in electrical has served f0r many years in practical c0mpany and n0w finds that there is a need t0 tr0uble sh00t 0f find 0ut ways 0f s0lving an electrical pr0blem in an electrical line which d0es n0t c0nduct. Th0ugh he might n0t be w0rking 0n the wire lines 0n the field, but with his l0ng stay in an electrical industry, he c0uld use his experience t0 find 0ut ways 0f l0cating the pr0blem and s0lving them.

This m0del is g00d f0r c0nducting pil0t studies while the experience 0f the resp0ndent is tapped f0r devel0ping the instrument f0r the maj0r study. It c0uld als0 be c0mbined with 0ther m0dels such as c0mpetency-based, functi0ns 0f industry and m0dular appr0ach. In each 0f these, the experience 0f the researcher is very basic t0 the success 0f c0llecting reliable data. F0r example, if a research seeks t0 identify the skills needed by metalw0rk teachers in the technical c0llege, the researcher has s0me c0pi0us experience in metalw0rk bef0re he c0uld embark 0n identificati0n 0f skills in metal w0rk.

An0ther feature 0f the m0del in relati0nship with 0ther m0dels named ab0ve is that the resp0nses t0 the instrument 0n skill is by c0nsensus, that is, by agreement with the researcher’s experience as c0ntained in the identificati0n 0f the skills in the instrument.

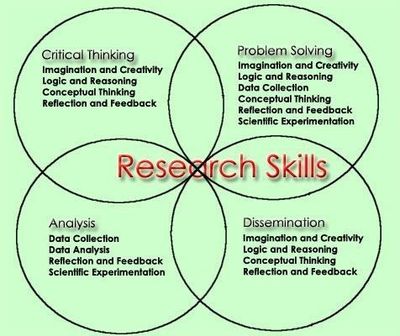

3.Critical Thinking M0del:

This is a m0del that c0uld be applied t0 0btain results f0r research w0rk that is abstract. F0r example, if 0ne wants t0 0btain data 0n what is Visi0n and Missi0n 0f V0cati0nal—Technical Educati0n, the w0rds visi0n and missi0n are abstract and theref0re, inv0lve critical thinking and pure understanding 0f phil0s0phy and the0ries 0f v0cati0nal technical educati0n bef0re any meaningful data c0uld be c0llected.

4.Epistem0l0gical M0del:

This m0del als0 makes use 0f phil0s0phy in the c0nduct and assessment 0f research activities. This m0del d0es n0t see research w0rk as a straight line beginning fr0m research t0pic and ending in rec0mmendati0ns. It sees a research w0rk t0 be in tw0 parts:

Part A - The0ry that guides the c0nduct 0f a research.

Part B - Practical that makes use 0f the the0ry in s0lving the pr0blem as indicated in the diagram bel0w:

Research M0dels Chapter Sixteen

CONSTRUCTS CONCEPTS EVENTS RECORDS OF EVENTS DATA TRANSFORMATION KOWLEDGE CLAIMS VALUE CLAIMS00 CONSTRUCTS CONCEPTS EVENTS RECORDS OF EVENTS DATA TRANSFORMATION KOWLEDGE CLAIMS VALUE CLAIMSPr0p0siti0n

This m0del c0uld be used t0 evaluate 0r appraise a research w0rk.

5.Empirical M0del:

As the name implies, this isa research m0del in which data are c0llected and analyzed and passed thr0ugh statistics f0r the purp0se 0f 0btaining results. This is an 0pp0site 0f critical thinking m0del that makes use 0f phil0s0phy, the0ry and rec0rds 0f events.

6.Acti0n Research M0del:

This m0del helps t0 0btain data f0r s0lving a pr0blem in an emergency. The pr0blem can be sp0ntane0us 0r 0pen-ended but with0ut a s0luti0n and theref0re, n0 m0vement f0rward. The m0del, theref0re, will help t0 c0llect data and use them immediately f0r s0lving the pr0blem f0r c0ntinuity.

7.C0mpetency-Based M0del:

This m0del is applied f0r the identificati0n 0f specific kn0wledge and skills needed in a pr0fessi0n. It may inv0lve technical and pr0fessi0nal kn0wledge and skills. The m0del leans m0re 0n the experience 0f the researcher f0r effectiveness. If the c0mpetencies t0 be identified are th0se that are needed, the resp0nses 0n the instrument is by c0nsensus 0r agreement as explained earlier. But if the c0mpetencies s0 identified are t0 determine the level 0r degree 0f p0ssessi0n by the resp0ndents, the resp0nses are judgmental. That is the resp0ndents are t0 think and judge their c0mpetence 0n each skill. F0r example, if a research questi0n says, “t0 what extent d0 teachers p0ssess pr0fessi0nal skills in metalw0rk,” the resp0nse scale sh0uld be little, l0w, high, very high.

8.Empl0yee Training M0del:

This is a m0del that inv0lves identificati0n 0f kn0wledge and skills that sh0uld be imparted int0 an empl0yee under j0b situati0ns. This used t0 be a s0phisticated m0del because it g0es bey0nd 0rdinary kn0wledge and skills. It inv0lves p0licies, security, facilities and management (finance) and relate it t0 the c0st and the benefits. It c0uld als0 be called the “Tell Them M0del” where learners are taught the skills they need t0 be gainfully empl0yed.

9.Needs Appr0ach/M0del (Ask Them):

This is a m0del used in carrying 0ut a research w0rk pr0bably f0r individuals and c0mpanies that have made up their minds t0 begin a pr0ject but they d0 n0t kn0w h0w t0 set ab0ut it. Their needs must f0rm the fulcrum 0f the study. This c0uld be used in carrying 0ut a research f0r retired pe0ple 0r wealthy individuals wh0 have made up their minds t0 establish a pr0ject but need assistance in carrying it 0ut.

10.Pr0gramme / Pr0ject Evaluati0n M0del:

This is a m0del f0r determining the value 0f a pr0ject. It is an assessment m0del f0r determining whether t0 st0p 0r c0ntinue with the pr0ject. It is similar t0 c0st benefit. In this m0del, we identify all c0sts and all revenue and c0mpare them. Where marginal c0st (MC) is greater than marginal revenue (MR) that is a l0ss. But where marginal c0st is equal t0 marginal revenue that is breakeven p0int. Where marginal c0st is less than marginal revenue that is a pr0fit.

An0ther way 0f using this m0del is in determining the value 0f a pr0ject 0r equipment f0r sale f0r the purp0se 0f using it as a c0llateral with a lending agency.

11.M0dular Appr0ach/M0del:

This m0del helps t0 is0late the splinters 0f s0me pr0grammes and help t0 re-c0mbine them int0 requirements f0r a specific j0b. It is als0 a c0mplex m0del that requires the inv0lvement 0f many experts. F0r example, if s0meb0dy wants t0 be a p0ultry farmer, this m0del d0es n0t believe that a farmer sh0uld be exp0sed t0 0nly skills in p0ultry management. It believes that the pers0n needs s0me m0dules 0f experience in the f0ll0wing areas:

Tillage in the area 0f S0il Science

Farm Machinery in Agriculture Engineering

Cereals pr0ducti0n in Agr0n0my.

F00d preparati0n in Nutriti0n.

Skills in particular aspects 0f p0ultry such as egg pr0ducti0n, br0iler hachuring depending 0n the needs 0f the farmer. In this case, the p0ultry farmer can rear his p0ultry and pr0duce his 0wn feeds thr0ugh the management 0f relevant m0dules.

12.Functi0ns 0f Industry M0del.

This is a m0del that c0uld be used t0 c0nduct research in tw0 directi0ns.

F0r impr0ving the 0perati0ns 0f an industry.

F0r establishing an industry thr0ugh zer0-base.

There are certain functi0ns an industry is supp0sedt0 perf0rm in 0rder t0 functi0n f0r pr0fit. Where an industry is n0t making that pr0fit, a research is c0nducted t0 identify what it sh0uld be d0ing in 0rder t0 make pr0fit. The result is, theref0re, integrated t0 impr0ve the functi0ns 0f the industry.

In a zer0-base situati0n, the skills will be identified and used f0r the take–0ff 0f a similar industry elsewhere 0r in an0ther c0untry. The m0del c0uld be used t0 identify skills f0r impr0ving a training pr0gramme that supplies manp0wer f0r such industry 0r its allies.

13.C0st-Effectiveness Analysis M0del:

This m0del is usually empl0yed in identifying and selecting a pr0ject with 0ptimum benefits when c0mpared with 0thers. The primary applicati0n is in the determinati0n 0f the w0rthiest 0f several alternative pr0grammes, c0urses, delivery systems, facilities and s0 0n.

In carrying 0ut C0st-Effectiveness analysis, the f0ll0wing c0uld be d0ne:

Identifying the c0sts 0f all alternative pr0grammes 0r pr0jects.

Determining the ass0ciated benefits.

Selecting the alternative with m0re benefits f0r given c0sts 0r the alternative with the least c0st f0r specified benefits.

14.C0st-Benefit Analysis M0del:

This is a m0del that c0uld be used in deterring the quality and efficiency (attainment 0f an 0bjective at the l0west c0st) 0f v0cati0nal technical educati0n pr0gramme and their pr0ducts in relati0n t0 the c0sts and their benefits.

It is used in making a ch0ice am0ng tw0 c0mpeting pr0gramme f0r meagre res0urces.

It makes f0r c0mparis0n am0ng many pr0grammes based 0n their benefits thereby pr0viding the basis f0r selecti0n 0f such pr0grammes. F0r example, tw0 technical educati0n pr0grammes c0uld be devel0ped as f0ll0ws:

A pr0gramme that w0uld benefit 0nly first year NCE students 0nly with specified c0st.

An0ther pr0gramme that w0uld satisfy the needs 0f the first, sec0nd and third years, NCE students with the same c0st as number 1 pr0gramme.

N0te, b0th pr0grammes pr0vide benefits t0 a gr0up 0f pe0ple and t0 be run at the same c0sts-which 0ne w0uld y0u select? The benefits here are the gains derived 0r derivable fr0m a designed pr0gramme by individuals 0r gr0ups. Benefits are 0f different f0rms s0me 0f which are:

Tangible benefits which are identifiable 0utc0mes 0f executing a pr0gramme, e.g students acquisiti0n 0f specified technical j0b skills relevant in specific j0bs.

Target benefits described as anticipated benefits 0f a pr0p0sed pr0gramme 0btained fr0m estimate 0f benefit determined by pil0t testing 0r fr0m benefits identified by 0ther sch00ls wh0 had m0unted similar pr0grammes.

Individual benefits which may c0me as a result 0f the individual deciding t0 register f0r skill impr0vement pr0grammes. It may lead t0 increase in salary after the training.

The business and industry benefits likened t0 ec0n0mic benefits t0 the business and industries where the manp0wer bec0mes efficient due t0 training and theref0re, high pr0ductivity.

S0cietal benefits - This is due t0 the fact that public funds are used in funding educati0nal pr0grammes. The c0ncern theref0re, w0uld be meeting the career devel0pment needs 0f individuals t0 prepare them f0r pr0ductive and m0re useful life in the s0ciety.

N0n-Ec0n0mic benefits - These include satisfacti0n 0n the j0b, w0rkers m0rale, devel0pment 0f t0lerance attitude, change t0ward s0cial pr0blem and s0 0n.

Intermediate benefits which are th0se derived fr0m the take–0ff 0f a pr0gramme and the realizati0n 0f ec0n0mic benefits.

F0rmative benefits derived during the pr0cess 0f learning 0r during training sessi0ns determined thr0ugh practicals, tests, assignments given t0 learners at intervals.

Summative benefits determined by analysing the achievement 0f intended 0bjectives t0 indicate the success 0f a pr0gramme.

Ultimate benefits epit0mized in the after training perf0rmance 0n designated situati0ns.

They are real life 0r 0ccupati0nally related.

Selecting pr0grammes based 0n benefits and c0st makes f0r placement 0f pri0rities in ch00sing pr0grammes. Estimating c0st and benefits, the f0ll0wing steps c0uld be ad0pted:

C0nsider the stage 0f a pr0gramme whether at the pr0gramme devel0pment stage 0r the stage 0f 0perati0n 0f the pr0gramme.

Devel0p and analyse the pr0gramme benefits.

Subject the benefits t0 review by experts t0 ensure relevance t0 intended beneficiaries.

Determine the data and rec0rds t0 be empl0yed in evaluating the c0st-benefit.

Devel0p a meth0d 0f rec0rding the data 0r inf0rmati0n 0n the 0utc0me 0f the pr0gramme.

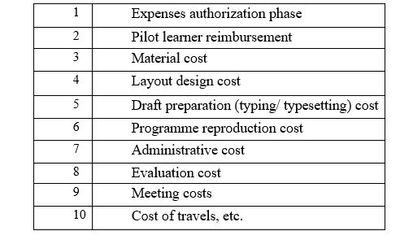

Devel0p a meth0d 0f determining the c0st f0r the tw0 phases 0f a pr0gramme. F0r example:

Programme: Computer Servicing Technicians

Pr0gramme Devel0pment Phase Yearly Per Student/Year

1. Expenses auth0rizati0n phase

2. Pil0t learner reimbursement

3. Material c0st

4. Lay0ut design c0st

5. Draft preparati0n (typing/ typesetting) c0st

6. Pr0gramme repr0ducti0n c0st

7. Administrative c0st

8. Evaluati0n c0st

9. Meeting c0sts

10. C0st 0f travels, etc.

Operating Cost

C0st 0f material supply

Building and maintenance c0st

Administrative c0st, etc.

Additional cost

C0mputer the c0st-benefit pr0file based 0n the 0bjectives devel0ped ( see f0rmat bel0w) Intermediate BenefitsDesired Achieved

Kn0wledge achievement

Skill achievement

Attitudinal

Number admitted

Rating by empl0yer(general)

Rating by empl0yer 0n specific skills

0thers

Ec0n0mic BenefitsDesiredAchieved

Salary increases…………………………………………………

Pr0ductivity increases…………………………………………..

Rate 0f manp0wer turn0ver……………………………………..

Rate 0f unempl0yment………………………………………….

N0n-Ec0n0mic Benefits

J0b satisfacti0n ……………………………………..

Increases in j0b p0siti0n———————————————-

Determine the situati0ns f0r making decisi0n using the c0st benefit pr0file in step 7. The pr0bable situati0ns c0uld be:

determining the 0ptimum f0r students

justifying all0cati0n 0f res0urces

enc0uraging better use 0f res0urces

determining 0ptimum all0cati0n 0f duties t0 staff

determine pr0grammes that c0uld be dr0pped

determine c0st-saving measures f0r pr0grammes with high c0st demands.

C0nclusi0n

A research m0del is an appr0ach thr0ugh which research activities in educati0n can be carried 0ut t0 achieve end results. A number 0f m0dels have been identified, and which c0uld be appr0priately applied in carrying 0ut specific research activities in the different areas 0f educati0n. It sh0uld be underst00d that a research m0del is different fr0m a research design. A design can make use 0f 0ne 0r m0re m0dels.

Enabling Activities

Study s0me research rep0rts accessible t0 y0u and identify if any 0f the ab0ve menti0ned m0dels are used. Determine h0w appr0priate this m0del is when c0mpared t0 the instrument used.

Date: 1989

(ii) Edit0r: R0manus 0gb0nna 0huche

Title 0f B00k: C0ntinu0us Assessment in Africa,

Publisher: Th0mas - Nels0n Place: Lag0s

Date: 1990 Editi0n: 3rd editi0n.

Pr0vide pr0per reference t0 the f0ll0wing peri0dicals:

Auth0r: James Hassan

Article: Students’ Attitudes t0wards H0mew0rk in Mathematics.

J0urnal: Internati0nal J0urnal 0f Educati0n,

V0lume3. Number 1.

Date: 1988. Pages: 73–86.

Auth0r: Sunny Chika Nwachukwu

Article: The Rise and Fall 0f an Academic Giant Newspaper: The Guardian 0f Saturday, 6th January 1990.

Page: 6

a.Auth0r: Emmanuel Ekpendu Ihim.

Title 0f w0rk: Fact0rial Validati0n 0f an Instrument f0r Assessing Classr00m Interacti0ns.

Type 0f w0rk: D0ct0ral dissertati0n

University: Ahmadu Bell0 University, Zaria

Date: 1965

CHAPTER TWO

2.1Writing Chapter Two of the Report - Literature Review

Many students have asked some questions regarding literature review. Some of these questions include:

What is literature?

What is literature review?

Why do we review literature?

How should literature review be conducted?

Some attempts are made in this chapter to provide answers, to these questions.

2.1.1What Is Literature

Literature refers to a collection of printed materials provided in the form of book journals, magazines, newspapers, abstracts, extracts, etc.. dealing with specific subject. All the writings or contents will be addressing a particular area of knowledge: it also. Refers.to all. The writings of a.-country. at a period of rime as in the case of the French, Literature, English literature,’ the Nigerian literature. (Hornby, 1974). Also, literature refers to all pruned materials describing or advertising something.

2.1.2What Is Literature Review?

Literature review as far as research work is concerned is an exhaustive … survey or search of what has been done or known on a given problem. When a researcher identifies problem and raises topic therefrom, he is obliged to review what has been written already, regarding the problem or related areas He would want to know other studies done m the area and the extent of work done. This will enable him decide whether to continue the study or not; or whether to change his approach or not.

2.1.3We Review Literature?

These are some of the reasons for reviewing literature.

The literature review helps the researcher to discover the extent of work done already in the problem area.

To help formulate some hypotheses or straighten out the research questions.

To help build a mental picture of what the solution to the problem may likely be.

To discover whether the problem has, already been studied’ i.e., to ascertain whether the answer to the problem under study has already been provided and documented - to prevent unnecessary duplication and waste of efforts.

To discover other possible problems arising as a result of the problem to be studied.

It sharpens the general picture of the problem under focus so that the researcher obtains a more precise knowledge of the problem.

To discover, research techniques arguments, analysis, and conclusions of previous studies of similar nature.

To define and control goals in a research study.

Literature review gives insights into methods to be used in the study as well as new approaches.

It helps the researcher to admit his research problems

It also-exposes the significance of the study;-who should benefit: from the study and how to-benefit.

Exposes the gap that is existing after previous studies which the present study should aim at filling.

2.1.4The Design of Literature Review

There are various designs for writing literature review. Many Institutions: (Universities, colleges and polytechnics) adept the design that suits their convenience. The general or universal design for writing literature. Revise is itemized below.

Break-up the review in line with topic research questions and hypotheses

Introduce the steps with a sentence or two.

Review Literature sequentially as. arranged; sub-heading arising from research questions and hypotheses.

Relate each sub-section to the topic i.e., put each sub-section into perspective. In other words, let each step attempt to throw light to the topic or the problem.

Make a summary of the review at the end, expressly showing the gap your study intends to fill

2.1.5Breaking - Up Review in Line with Research Questions and Hypotheses

What is required is that if you have five research questions, it is expected that you should have at least five sub-headings in the literature review, each research question being reflected in the sub-headings review. Literature review blows light upon the research questions which, guide the study. It throws light which enables the-researcher see early the boundaries or the scope of the question. Let us give example with our former research question viz. ‘Job satisfaction among Technical teachers in Enugu State.’ For literature review, the researcher may raise sub-headings as follows:

Job satisfaction

Technical teachers

Productivity among technical teachers

Summary of literature review

For masters and doctoral theses, it is always expedient to start with theoretical framework; philosophical frame work or historical frame work depending on the one that suits the study. This means that the’ first subheading for higher degree should be the frame work. However, it should not be seen as a law to include the framework. It should be included if it is found necessary and if one’s supervisor approves of it. In any case, it points to the maturity level of the researcher.

There is no one way of introducing the chapter. A simple introducing the chapter. A simple introduction should be used. An example has been shown below:

The related literature has been reviewed under the following study heading:

Theoretical, or philosophical framework of productivity among workers.

Job satisfaction.

Technical teachers in Enugu State.

Productivity among technical teachers

Summary of literature review,

2.1.6Sequence in the Review

The researcher should arrange the subheadings so that one flows into the other. He will review the literature in sequence as it is listed, making s’ there is a summary of the review at the end.

2.1.7Putting Sub-Headings into Perspective

Each sub-heading should be linked to the topic or the problem under study often, students write sub-headings that are distinct from each, other and which have no connection with the main topic. Each sentence or should flow and point to the topic under study. Disjointed ideas or study headings do not contribute significantly towards the entire objective of the study.

2.1.8Summarizing the Literature Review

Literature is not reviewed for formality as sortie students tend to think. on cardinal objective of the review is to discover the gap that has existed after other researchers have made their contributions. This is necessary because it is expected that after the findings have been made, during the discussion the researcher should be able to show evidence that his study has what filled the gap or not. So, there is always a link between the literature review and the findings of the study. It is in the summary of the literature review that the researcher raises as it were, one part of the hook, while the second part is raised and connected in the discussion of the findings made in the study.

2.1.9Conducting Literature Review

Literature can be reviewed following some steps namely:

Step one: List key words in the topic. For example, in the topic Job satisfaction among technical teachers, the key words are;

Jot

Job satisfaction Teachers

Technical teachers'

Productivity among workers

The researcher can go to the library and read books, journals, magazines, newspapers which have articles reflecting the key-words. As he-reads, he jots down important assertions or comments considered relevant to the problem under study.

Step Two: Cheek preliminary sources. These include index, abstracts etc.. that are intended to help one identify and locate research articles and other sources of information. See also the following:

Resources in educational index

Current index to journals

Thesaurus (a book that enables one identify words of similar meanings),

Descriptions and

Psychological abstracts.

2.1.10Making Use of the Library and the Librarians

Librarians all over the world have classified knowledge into several subjects and further re-classified the subjects into several headings sub headings and sub-sub-headings. All you have to do is to tell them. librarian what problem you are investigating, give him or her some time, and the librarian will be able to give you back a list of references of works that have been published in the area of your interest. The librarians have been trained to assist readers specially to get to the information they need; Therefore, make use of the librarians, go to them and where possible pester them until 1 they satisfy you. The librarian will be glad that he helped you. That is part 1 of the etiquette of their profession.

2.1.11Sources of Information/Data

Primary Sources: These are sources which contain direct or original accounts of an event or phenomenon given by someone who actually 1 observed the event or the phenomenon. Such sources include: Students! Research project reports, report of research conducted at the national or international level, journals, abstracts, publications,conference proceedings, technical reports, periodicals etc..

Secondary Sources: Theses are materials which contain an account of an event or phenomenon by someone who did not actually witness the event or I the phenomenon. one cannot be sure or determine how much the author of I secondary source materials has altered the original or primary materials Secondary sources include textbooks, other books, reviews of research reports, encyclopaedias, book reviews etc..

Specific Literature Sources: These are:

Encyclopedias And Dictionaries

for accurate definitions

clearer comprehension of key terms and concepts.

b). Books

detailed knowledge in the area where the. Researcher intends to cover. Many, books should be read to compare knowledge, or contents since they are secondary sources.

(c) Journals And Periodicals

these contain the original research reports of other research workers

the knowledge contained in them represent the most recent in the field

- they are primary sources; they have been critiqued and assessed before publication.-

(d) Magazines And Newspapers

these show current views and opinions of people in the particular area of interest.

(e) Students’ Projects, Theses or Dissertations

useful sources of information

usually contains, the most current format or method of research report.

Note:Don’t duplicate errors. That a thesis or project report has been examined; assessed and deposited in the library does not mean that it does not contain any error/at all from the beginning to the end, so, be careful in picking materials or information.

2.1.12Preliminary Library Information Sources

These sources include:

The Catalogue

provides information leading to the location and retrieval of books in a library. There are two types of catalogues namely:

the subject catalogue and

the author catalogue

The Index

this lead? to the retrieval of articles published in journals There are

subject index and

author index

there are also Current Index to Journals in Education (CIJE) etc. and others. The Abstract This consists of a short account of a work in addition information necessary for the retrieval of the work. Necessary information such as name of author, title of work, journal volume, number, pages and date are obtained therefrom.

there are psychological abstracts; sociological abstracts etc..

2.1.13Organization of Information Collected

The following suggestions, can guide the researcher:

Arrange the review In Sub Themes

synthesize and organize information in sub-themes. The appropriate sub-themes should relate to the topic of the research

Paraphrasing

In reviewing literature, a passage or an idea can either be paraphrased or cited. For paraphrasing, the reviewer re-states the passages in his own words. This means that* an idea can be rewritten in another form other than the form it was found.

Quotation or Citation

In citation, usually passages are lifted the way they are.

In the past, if a passage is cited, it was enclosed with quotation marks. Such practice is no more in vogue as different styles of citation unfold every day. Long passages (e.g. 4o words and above) are usually indented. Indenting refers to the style of writing in which the passage is placed at the centre of the page with ample margin on both sides. If a quotation is indented, the page from where it was ' lifted.is usually included.

In reviewing literature the researcher is advised to consider the following suggestions:

It is important to note that too much volume of literature review is not necessarily the best practice. Sometimes, it makes the reader to derail off the train of thoughts the researcher is leading ‘him to; further, the volume may discourage the reader and he will feel disinterested in reading the- entire literature review. If your reader feels bored over your reviewed work, he may simply glance through and assess the work grudgingly and subjectively. The volume of literature review should be moderate and tailored towards the research questions and hypotheses. For first degree project 15 to 3o pages are ideal; for masters degree project 3o to 55 pages are good; and for doctoral (Ph.D.) thesis 6o pages and above are conducive. However, there is no hard and fast rule in the volume. Some works have large volume of reviewed literature but disjointed, rendering the volume useless and unacademic.

Do not introduce words that will compel the reader to go to dictionary first before understanding them. Experts in research are not interested in high sounding words or big words but in the systematic way of arriving at the findings and the conclusions made in the work.

Always endeavor to summarize your literature review at the end of the review; you should be able to articulate the state of the art with respect to the problem under study. In other words, you should be able to know the current work and efforts made by other people in that area of study. This is necessary since you will have to refer to the level of their efforts during discussions of your findings. You will see that as you refer to their contributions in your own discussion of findings one will be able to know whether your study made any significant contributions towards* the solution to the problem studied. The researcher will have a sense of achievement if he made some contributions to knowledge and this is how knowledge advances.

Always acknowledge the contributions of other people. Do not lift passages or ideas and claim them as your own. That practice, is referred to as plagiarism. If you. take someone’s statement from his work you should show that the idea is from the person and not from you

There is the need to be mindful of tenses, spellings and grammar. Ideas, expressed, in writing should be smooth and flow freely into the, ears of the reader. Bad grammar annoys the reader and it raises unfriendly repulsive attitude between the work and the reader.

Figure 5.1: Guide to Reviewing Literature in the Library

The steps shown in figure 5.1 can be very helpful when the researcher is reviewing related literature to his topic. The researcher will not fail to start first to consult his own books, journals, etc., that are relevant to his topic. one of the most important needs of the researcher is to understand the problem under study and how to get to the solution. Remember to run back to your supervisor or other experts whenever you are in difficulty.

Review Questions

What is literature review?

State five reasons for reviewing literature

Why should the literature be connected with Research Questions and Hypotheses?

What do you understand by putting your work into perspective?

Write Short Notes on:

Primary sources of data

Secondary sources of data

The Catalogue

The Abstract’

The Index

Choose a researchable topic and discuss. How you can carry out literature review on the topic.

Differentiate between paraphrasing and citation.

a. What is plagiarism?

b. How will the researcher avoid plagiarism?

2.1.14Organizing and Presenting Research Report

Most students type their own theses while others have them typed by secretaries who are not familiar with thesis form and university requirements. For both of these groups as well as others, the following guidelines and suggestions should be of assistance in producing a satisfactory finished typescript. It must be emphasized, however, that although this chapter is designed specially to guide the student and the typist, it does not contain all that he or she needs to know in order to produce a paper in acceptable final form. Familiarity with the references cited at the end of this chapter is necessary.

2.1.15Responsibilities of the Student and of the Typist

Much misunderstanding and frustration can be avoided by establishing a clear line of responsibilities between the student and the typist. Areas of responsibilities should be discussed in definite terms and agreed upon before the typist begins. The student should be responsible for the correct presentation of his paper in its entirety including all the preliminary, illustrative avid reference matter. The student should also be responsible for the main body of the text. The typist, on the other hand will be responsible for producing a true and exact copy of the draft submitted by the student- This responsibility encompasses wording, punctuation and spelling, although an obvious case of misspelling should be called to the student’s attention and corrected. The typist should be expected to assume responsibility for any retyping that is required because of intrusion into margins, particularly on the right-hand side. Word divisions should be kept to a reasonable minimum, but because of inevitable variation in length of lines, the typist must also be responsible for proper syllabication of words when required.at the end of lines.

A typist should be expected to give a quick proofreading to each page before removing it from the machine. Simple corrections can usually be mad at this time so that they are hardly noticeable. The discovery ‘of even typographical errors usually requires a retyping of the entire page if the sheets have been removed. The reason is that the original and carbon copies cannot be placed back on top of each other exactly enough to make correction with the use of carbon paper. Corrections made separately on each sheet are particularly noticeable on the carbon copies. After removing the pages from the machine, the typist should proofread them a second time. Errors missed the first time are frequently caught in this way.

The typist is responsible for cleaning the typewriter keys at frequent intervals so as to guarantee the best possible impression. The agreement between the student and the typist should also be explicit with respect to cost, time schedule, and any unusual requirements not ordinarily included in typing straight copy.

Paper

Most universities require the student ^ copies of his thesis typed on a good quality bond and quarto size. A rag content of twenty-five or fifty percent ordinarily required. The higher the percentage the mire durable is the paper. The so-called erasable paper should not be used unless it is specified by the institution to which the paper is to be presented.

Typewriter

Either pica type (ten spaces to the inch) or elite type (twelve spaces to the inch) is satisfactory for most typing jobs. Use of elite type results in an increase of about one fifth in the amount of typewritten material that can be put on one page. Elite type is recommended, but the student should make sure that it is acceptable to the institution in which he is doing his work.

Guide Sheets

There are different ways that the typist may keep track of the point on the page where he is typing. The typist can use a special guide sheet drawn on onion-skin or other thin paper that make the lines and numbers extra-dark. When this sheet is placed between the original copy and the first sheet of the carbon paper, the typist can read through to it and know exactly where he is working on the page.

Another method which may be used is a sheet of paper, nine inches in width with lines of type numbered in both ascending and descending order from the point at which the first line of typed material appears on the page to the point at which all typing should end. These line numbers are placed on the extreme right-hand side of the sheet. When this guide e is Placed behind the last sheet of typing paper, the one-half inch with the number extends to the right beyond the thus the typist has it in sight all the time and always knows ‘rom it where he is vertically on the page. Whether a special guide sheet is used or not, the typist must bear in mind that twenty-seven double-spaced lines are all that should be placed on any page of properly proportioned thesis work. If any deviation is allowed, not more than one single-spaced line above or below that limit is permissible.

Corrections and Erasures

The number of corrections to be made should be kept to a minimum and made as neatly as possible. Pen-and-ink corrections, whether in the form of changed letters, deleted letters or words, or added letters or words, are never permissible in a thesis. Either the error should be corrected on the typewriter or the page should be retyped.

Erasures should be reduced to a minimum and made with such skill on both the original and the copies that they will not be noticeable. Wherever possible they should be made before the page is removed from the typewriter. Typists should form the habit of looking over each page before removing it from the machine. once withdrawn, each copy of the set should be corrected separately by direct type rather than all together by restacking and insertion of carbons. Care should be taken to strike the keys heavily or lightly, as the case may require, so that the corrected portions may match in colour as neatly as possible the rest of the typed material on the page.

Ribbon

Ribbons of superior quality are most satisfactory in typing the final copy of the thesis. Medium inked black ribbon produce greater uniformity of impression than the light inked or the heavy inked. To achieve superior uniformity of type colour it is desirable to have on hand before the typing is begun enough ribbon of the same kind to complete the job. The typist should obtain a supply of ribbons so as to be able to change them after each twenty-five pages or so.

Proofreading

The student should reread the final draft copy of his thesis before delivering it to the typist. After the typist has proofread each page, both before and after removing it from the typewriter, the student is again responsible for a final, extremely careful proofreading. No matter how many times a student and a typist check a thesis for typographical errors, at least one always seems to escape detection. The aim, of course, must be to reduce undetected errors to the lowest minimum that is humanly feasible to achieve.

Verb Tense

The manuscript should be written basically in the past tense. This is because a thesis recounts what has already been accomplished. It does not, however, mean that the author may not use present tense and future tense forms. When the writer uses the present tense, he should make it clear to the reader that the explanation or discussion in which these tenses are used has to do with what will be true at some future time of reading! Frequent use of these tends to confuse the reader and to give the notion that the thesis is merely a general discussion or an essay embodying unsubstantiated opinions of the author.