CHAPTER 20

GENETIC RELATIONS, HISTORY AND LINGUISTICS A RECONSTRUCTIVE HISTORICIZATION

Charles Okeke Okoko, PhD

Introduction

“As truthful as the genes” underscored the assertion that languages shared, and still share, a common ancestorship from a proto language. That languages were formed and spoken by people meant that their origins vis-a-vis their present locations or settlements could be traced through linguistic comparisons. Premised on the “Family Tree” model, the assumption was that languages and their speakers dispersed from an original homeland where the proto-language was spoken. As fissures and dispersals went on, speakers of the original language picked up and adopted certain characteristics not common to the other offshoots from the same proto-language area. Referred to as innovations, these were in the forms of changes in sound (phonology), grammar and vocabulary, especially in the non-basic. Invoking the principle that nothing originated in a vacuum or in isolation, the thesis concluded that linguistics was, and still is, a veritable tool in interdisciplinary research for the historian; and that the study of historical linguistics was to be pursued with vehemence and vigour and taught in all history departments, in association with departments of linguistics, of Nigeria’s tertiary institutions, where it was, and is, not done.

This thesis seeks to re-emphasize the need to fully grasp the contents, perspectives, philosophy and methodology of African history. This re-emphasis is based on its importance since Africa has been a stage upon which the “drama of human development and cultural differentiation has been acted since the beginning of history”.

As mentioned earlier, from the times of David Hume, Hegel through to Hugh Trevor-Roper, representing different historical epochs, African history has faced distortions and presented as unworthy of any kind of academic study. It was rather premised on Eurocentrism, which labelled Africa as the “Dark continent” waiting to be discovered by the Europeans. While these theories have been motivated by the need to justify the continued domination and exploitation of Africa by the Europeans, it was nonetheless necessary to evolve the best methods that would be used in the writing of African history. Although Africa had some written forms, even as signages, colonialism marked an important watershed during which the Europeans introduced innovations, such as Christianity and Western education that played significant but certainly not an overwhelming part. Basil Davidson once asked, “Can We Write African History? Kenneth Dike, E. J. Alagoa, Ade Ajayi and Ali Mazrui, to mention a few, as mentioned in the previous chapter, seemingly answered in the affirmative with titles, such as “The African History and Cultures in the Process of Nation Building in Africa” and “Africa Discovers Her Past.”

The students of African history became faced with the challenge of writing the history of the non-centralized states that were regarded as insignificant parts of the historical world, in all its complexities. By this time, African studies had become a subject of academic interest in African tertiary institutions. Departments for its study were started in many of her universities, and even overseas. The ‘Africanists’, as the first crop of anti-colonial historians were referred to, undertook the writing of African history with zeal. But they were immediately challenged with obstacles regarding the methodologies to be used, in their attempts at writing the histories of non-centralized societies. There were no written materials to be used in the process. Moreover, the Africans trained in Western historiography regarded the study of non-centralized societies as a waste of time. It was a considered opinion then that it would be unimaginative to attempt the writing of the histories of communities not yet in print. They argued that such a work, if ever produced, would amount to a bundle of guess works. Yet, there remained so much in the past that are unknown. Should the heavy work envisaged in this task depreciate their importance? Robin Hallet has pointed out that: “To brood too long on these limitations is simply to discourage action” and court lethargy in the historians.

A certain degree of certainty could be attained through the application of the interdisciplinary research approach. This method became necessary in order to curtail the dilemma faced by African historians in the writing of their history in the post-colonial period. This was even made more problematic by the paucity of materials available for research. The interdisciplinary research approach has entailed using other disciplines, such as archaeology, anthropology, ethnography, ethno-botany (to determine probable origin of crops), sociology, linguistics, paleobotany, paleozoology, and physics (through radiocarbon dating) in reconstructing the past histories of communities without writing culture.

Before the adoption of the interdisciplinary re-search method, the only fodder for research was the peoples’ folklores which were referred to as oral literature or ‘orature’. With time, a compendium of oral histories, some lacking in conviction was compiled. Thus, there arose the need to subject oral literature to critical analysis and look for other measures to be adopted in writing the histories of acephalous communities.

Linguistic Analysis Using the Family Tree Model

Referred to as the Geography of Linguistics this technique is used to delineate spatial relationships of languages and the dispersal of their speakers from a probable homeland; and how they have spread out. Put in another form, it is directed at charting the spatial courses of their subsequent expansions and dispersals.

Fissures, dispersals and migrations from one point to the other are underpinned by natural and man-made disasters. In the process of the shifts, the speakers of a proto-language picked up innovations into their sound (phonology) and grammar, and adapted them into their language, from other languages. Although man is conservative in adding new ‘things’ to his natural system, innovations introduced from outside or impinged on them have, however, been added, although often imperceptibly. But in terms of culture words, for instance, these have found themselves in the non- basic category.

Regarding linguistic theories and methodologies, the basics are assumptions and deductions based on the “family tree” model. The linguist simply decides through comparative analysis of languages which area is the old territory of a language-family and the new. The “family tree” model asserts that, the longer two daughter-languages are separated, the greater the differences between them in terms of differences and similarities in their basic vocabulary. The changes that take place in their sound (phonology) and grammar are called innovations. Some innovations spread widely within a language, others re-main confined to a few villages. The spread of an innovation is sometimes compared to the dropping of a stone in a pool; a little wave from the point of droppage will spread out in all directions. If two stones are dropped at different places, the two waves may meet or not and exist independently with increasing distinctness.

Identifying Homelands, Changes in Sound and New Areas of Settlement

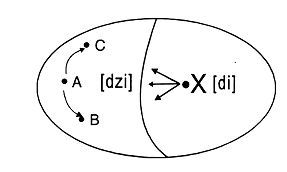

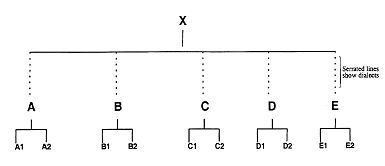

This section attempts reconstructing the possible changes that would have occurred in new languages that dispersed from a proto-language area. From Figure I, the area covered by ABC has acquired a change having dispersed from X. It has added an innovation in sound from [di] to [dzi]. The whole area formerly pronounced the sound as [di] but now as [dzi]. Thus, the other part of the entity not covered by ABC still retained [di] in their pronunciation and, therefore, remains the original homeland.

The line separating the two areas: ABC and X is called an ISOGLOSS. A bundle of ISOGLOSSES results to dialects or dialectical differentiations. As the new dialects that have been formed or originated as a result of fissures and dispersals encounter and adopt further innovations they develop into distinct languages. It must be pointed out that languages, although evidentially distinct, that have been in constant communication and contact by their speakers are, often, not affected by the encroachment of innovations or the effects of intervening variables.

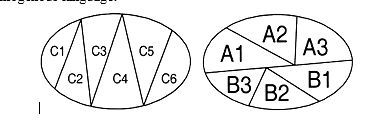

Moreover, a dialect must belong to a larger language unit in a particular place or area. For instance, Onicha is a dialect of Igbo language, while Ijebu is a dialect of Yoruba language. But for intelligibility to persist in the dialects of a language, there must exist avenues, no matter how slight, through which the speakers of the dialects continually interact and understand each other. This situation results to a dialect chain. For instance:

It is important to point out that the size or population of the speakers of a particular language, if small, cannot make it a dialect and must be regarded as a distinct language from other contiguous languages with larger populations of speakers, evenso, when there is no dialect chain as shown in Figure n. There have been discovered cases or regions where dialects were mistaken for languages especially when there was, and still is, no name for that group of dialects. For instance, unlike the Igbo, Hausa, Edo and Yoruba languages, the dialects spoken by the Agwa’gwuna, Adim, Erei and Abini in the Cross River valley do not have a group name. Yet, the speakers understand each. This development has been referred to as a ‘Dialect cluster’. Presently (2016), these dialects have remained as clusters with none evolving into a distinct language that could be described as unintelligible to the speakers of the other dialects in the cluster.

Another situation is where members of a group in a particular region do not understand the various languages spoken within it clearly. At times, claims are made regarding who borrowed aspects of vocabulary (basic and non-basic) of a language from the other. This is referred to as a ‘Language cluster’. For instance, although the Nembe and Kalagbari are ancient contiguous neighbours, a comparison of the two languages showed arelationship that is highly distinct, implying that they separated from each other from a homeland in the remote past: But who separated from the other? Further examples of language clusters are the Yoruba and Igala; the Kana and Eleme in Rivers State; and the English and German who belong to the proto-Indo-European phylum (sub-branched under the Germanic).

Summarizing this section, some dialects after having been impinged upon or unconsciously acquired visible and distinguishing innovations; and after many years of separate existence, are known to have developed into languages. Ad infinitum, these languages in turn developed into language groups which also formed language branches and then to language families. These stages of language formations and disintegrations have been traceable, eventually, to a proto-language and to a geographical area.

This way, too, the historical origins of the languages and speakers of the languages have been traced to specific regions or proto-sites where semblances of the original language or languages are spoken. But to arrive at meaningful deductions in the reconstruction of the origins of speakers of particular languages and/or dialects, analyses have always been premised on some factors by the linguists, namely:

The relationship between, and the fissures within, and dispersals by, the languages in the past or remote past; and

The positioning of the languages.

For instance, if the languages are found positioned adjacent to each other, it is inferred that they are likely to have derived from the same proto language.

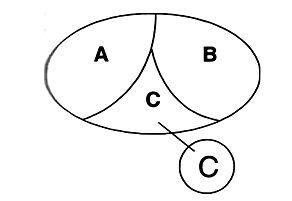

As indicated in Figure IV, ABC are sister languages and have X as their proto-language. Supposing C migrated to another locality as shown in Figure V, the evidence to show that it dispersed away from A and B is that it is simple and natural for a single group to move/migrate than it is for two groups to move/migrate at the same time. The general principle is that the area that has the most distantly related languages, after a comparison of their basic vocabulary, is likely to be the area of origin or the homeland of variants or dialects of a proto-language.

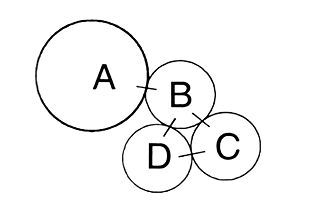

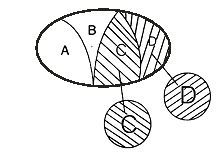

Consequently, evidence in Figure VI portrays AB as the original homeland because the territories have the largest numbers of distantly related languages when compared to C and D. Therefore, in comparing linguistic diversities and similarities in order to determine neo-locality and the original homeland, it can be inferred that A and B are most distantly related while the same comparison in C and D show that they are closely related which is indicative of a recent break off. A and B have high language diversities while C and D have low language diversities.

Similarly, further inferences could be drawn from Figures VH and Figure VUE (below), which are the same and propose that C migrated alongside AB from the original homeland. The assumption is that A and B have lesser number of diversities/-dissimilarities, and are distantly related languages, while C has more recently separated languages and, therefore, has lower diversities and are more closely related than are the languages in A and B.

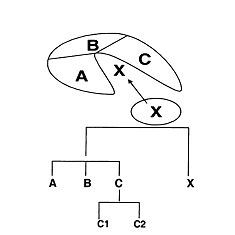

It is also possible to identify an intrusive community or language through linguistic comparison of the language groups in an area. For instance, in Figure IX (a): A, B and C are related languages, whereas X is a new or intrusive language that its speakers settled among ABC. The following assumptions are made in order to deduce that X is a recent or intrusive language, namely, first, through the relationship it has with the other languages. From Figure IX (b), although Cl and C2 might have developed different dialects and acquired differing innovations, they are still part of theproto-C, therefore, are of the same language while X is a homogenous language that has not diverged, broken into or begotten other languages; and second, while ABC are seen as distantly related languages and Cl and C2 are seen as closely related to C of ABC, X remains a homogenous language.

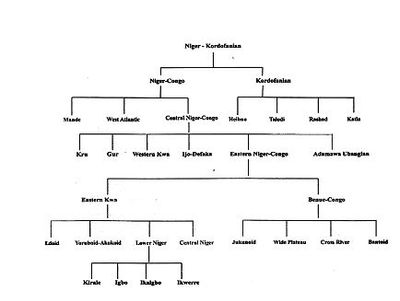

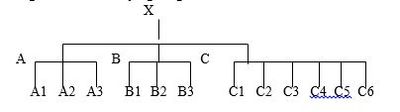

The assumptions and inferences made from Figures I to IX, are based on the family tree model, which after classifications by +J. H. Greenberg, Bennett and Sterk and Kay Williamson, show that languages always originated from a proto-language and a homeland. From the family tree below, certain assumptions and deductions have been made to include:

ABCDE are daughter languages that originated from X which loci is the homeland;

ABCDE are sister languages because they share an immediate proto-language X; and

ABCDE are, in turn, the proto-languages of A1 A2; B1 B2;

Related Models of Linguistic Comparison and Analysis

Although several models of linguistic analyses geared towards historical reconstruction have been mentioned and studied, there are other related models that, often, cannot be employed in isolation of others. However, emanating from, and based on, the “Family Tree” model are Lexicostatistics and Glottochronology processes.

Lexicostatistics

Lexicostatistics entails the systematic comparison of the basic vocabulary (that is in respect of that portion of the vocabulary referring to universal and unchangeable aspects of human experience in communities) of sets of languages whose speakers are believed to have a common origin. It is equally premised on the fact that since resemblances in basic vocabulary of different communities are not due either to coincidence/impingement or to borrowing, it follows by elimination that they are most likely to have occurred due to common origins. Given the “Family Tree Model’ assumptions, it follows that a relatively high percentage of similarities between semantically equivalent items of basic vocabulary in any two languages indicates a relatively recent separation and a common origin, while a relatively low percentage of similarities indicates a relatively ancient period of separation of languages and their speakers and, definitely had a common origin in the very recent or remote past. This way, successive differentiations in the original proto-language area that gave rise to the set and of the successive dispersals of populations underlying the successive differentiations can be reconstructed.

Glottochronology

Glottochronology attempts to replace the relative dating method of language differentiations and population dispersals offered by lexicostatistics with a form of absolute chronology. But this method, while it has been applicable to the study of Igbo origin through linguistic data, is essentially applicable to languages whose pasts have been preserved in writing for over some two thousand years. It is assumed in this process that in any language, items of basic vocabulary are dropped and replaced at a constant rate. This rate is roughly the same with all languages. When sections of a human population undergo physical and social separation, the incipient daughter languages continue to undergo lexical changes at the same rate. But the sets of items dropped or replaced are not the same in the various cases.

There is always a progressive divergence of the basic vocabulary of the various daughter languages, and this -divergence, too, develop at a constant rate. It follows that, for every period of time since the beginning of differentiations within a pair of daughter languages, there is a corresponding percentage of similarities in basic vocabulary. So, working backwards from the percentages supplied to us by the lexicostatisticians, approximate absolute dates from the beginning of differentiations in pairs of daughter languages, and from the time of human separations underlying these beginnings, could be arrived at. But this method is fraught with uncertainties and misgivings since there is, yet no definite consensus on the rates of change and divergence.

Linguistic Classification of African Languages and Original Homelands

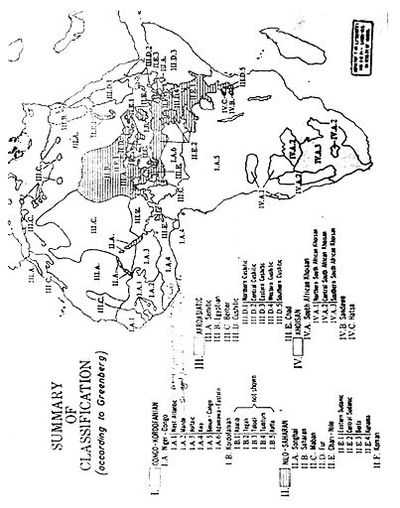

J. H. Greenberg classified African languages into four major phylums, namely:

The Niger-Kordofanian which has the Niger-Congo and Kordofanian as major sub-phylums;

The Nilo-Saharan that extends from the Nile to the Sahara through to East and Central Africa;

The Afro-Asiatic which are spoken in parts of Africa and the Near East, and inclusive of Arabic and Hebrew; and

The Khoisan which are spoken in the North, Central and Southern Africa, and inclusive of Sandawe and Hatsa.

The Niger-Kordofanian/Niger-Congo

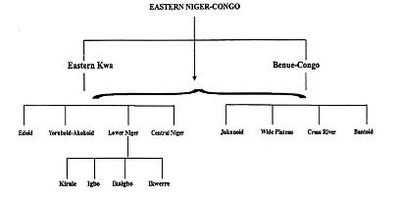

Of particular interest to this thesis are the Niger- Kordofanian and its sub-phylums, families and groups. Greenberg’s classification was modified in a presentation by Bennett and Sterk during the 19 Language Congress at the University of Ibadan in 1977 to three (3) sub-families instead of six (6), namely, the West Atlantic, Mande, Voltaic, Kwa Benue-Congo and Adamawa- Eastem (see Figure XI). Also Kwa was split into two (2) sub¬families and which Bennett and Sterk classified as Western Kwa. In the revised classification, Eastern Kwa was merged with Benue- Congo to form Eastern Niger-Congo. Thus, the Eastern Niger- Congo comprises the Eastern Kwa and Benue-Congo.

Further contextualized to this chapter is the Lower Niger sub-family which comprises Kirale, Igbo, Ika Igbo and Ikwerre. While it appears the historian apes the linguist in the usage of linguistic data, it broadens his scope for research and authority. The tracing of homelands of languages and the origins of the speakers of the languages would also be known. This has been predicated on the reconcilable fact that every community has a language, even when it is a sign language.

As mentioned earlier, most communities dispersed from somewhere that could have been their original homelands to other places as a result of natural and man-made factors. These shifts are underpinned by the encroachment of innovations some of which are adopted and adapted into their original milieu. The shifts affect human conditions generally, inclusive of their languages. Regarding natural disasters, speakers of languages have tended to migrate in response to changes in their environment. Described as another ‘Aquatic Saga’ by Robin Horton, linguists, anthropologists and ethno-historians agree that the climatic condition and eventual desiccation of the Sahara contributed immensely to the movements of language groups away from the region.

Before the desiccation of the Sahara region, it is assumed that the homeland of African languages was to the North during the ‘wet’ period (pre-desiccation), then the speakers of the languages separated during the dry period. While Greenberg had surmised eastwards and southwestwards movements which implied that two (2) groups were involved, Bennett and Sterk suggested three (3) movements during the dry period. The first was to the east by the phylum referred to as the Niger-Kordofanian; second, to the west, by the phylum referred to as the Mande; and the third, by the phylum referred to as the Niger-Congo. But Greenberg insisted that the Mande separated from the Niger-Congo homeland in WestAfrica and not as a distinct language family as implied by Bennett and Sterk’s classification. Methodically, both schools of thought used the lexicostatistics and glottochronological comparative methods that are in turn based on the Family Tree Model to arrive at the conclusion that the homeland of the Niger-Kordofanian proto-languages’ phylums was in the Sahara region before the desiccation period started.

Rigorous comparative studies have been conducted in attempts at tracing the origins of the languages that are spoken in the West African sub-region and the evidences that have been inferred informed the, or gave credence to the, conclusion that they all originated from the Niger-Congo which have proliferated/dispersed as the Mande, to the West Atlantic and then to the Central Niger-Congo (CNC); and subsequently into all the languages spoken across and beyond the Economic Communities of West African States (ECOWAS). From Greenberg and Bennett and Sterk’s classifications, is found the Lower Niger which is a sub¬family of the Eastern Niger-Congo and to which Igbo language is a sub-division. This introduces the next section of the chapter that surveys the origin of the Abam of the Cross River Igbo area through linguistic comparison of culture words.

The Origin of the Igbo: The Abam Example

Abam is one of the matrilineal Cross River Igbo martial communities alongside the Ohafia, Edda, Ihe-chiowa and Ututu, among others. Abam itself is situated to the east of Umuahia and Bende, to the northwest of Arochukwu and to the southwest of Ohafia and the Edda respectively. The Abam occupy the territory further west of all the Cross River Igbo. It has an estimated area of 80 square kilometers, bounded approximately by latitudes 5°20' and 5°30' north and longitudes 7°40' and 7°45' east.

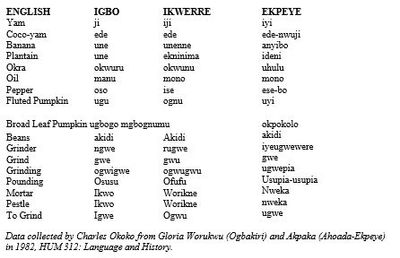

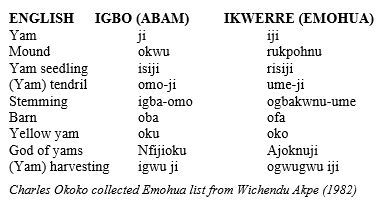

The method used in determining the origin of the Abam is the comparative analogy of languages, dialects and phonology which was aimed at delineating patterns of similarities and differences; and the analysis was based on a consideration of a number of generalizations concerning the ways languages were affected by the splitting and dispersal of human populations. Notably were the changes in vocabulary, especially in the non-basic vocabulary, pronunciation and in grammar. The languages of the dispersed population first divided into dialects and after about a thousand years became two distinct languages. In the comparative study, emphasis was laid on the basic vocabulary of the communities since people tended to stick more to it than to their non-basic vocabulary into which were continually added new experiences/innovations in preference to non-current culture words.The Igbo language belongs to the Lower-Niger language family. Following the principle of homeland location which states that the area maintains the most distinctly related languages is likely to be the proto-homeland. After the comparative analysis of culture words from the languages of the Lower Niger group, it was inferred that the probable homeland of the Igbo speakers was around Ekpeye community in the Ahoada Local Government Area of Rivers State. The agricultural products, foods and preparatory implements and yam cultivation among the Igbo (Abam), Ekpeye (Ahoada) and Ikwerre (Ogbakiri and Emohua) were compared and analysed.

From Figure XIII, it is clear that there is a relative degree of firmness or coherence from the reconstructed culture words and thus has been able to infer an old culture element. The languages, though it is difficult to call them so, fit into one geographical environment and they tend to cluster towards the south around Ekpeye (numbered 95, see Map XII), which probably understood each other at their proto-stage. However, there have been changes in the sound systems of the languages due to separation and innovations. In such changes we see [kw] as in okwuru in both Igbo and Ikwerre having changed to [hu] in Ekpeye. However, these are still cognate but have contributed to changes in phonology. Since the speakers dispersed from a common homeland, they have simple words, which cannot be reduced further. Such words are for yams, cocoyams, banana, okra, oil, pepper, fluted pumpkin and beans. There are, however, compound words, which still maintain their simple words, for instance, we have edein both Igbo and Ikwerre, but - nwuji - has been added to it in Ekpeye.

Figure XIX shows, again, a common origin since only phonological and grammatical changes have occurred. It is thus possible to, through linguistic comparison of culture words, establish the homeland of different communities/peoples with different languages. But the com-pared languages do not seem to have diverged enough to merit the status of languages but could be described as distinctly related dialects. Although the glottochronology method has been effective with written languages, the method can be applied to equally old languages spoken in areas that did not have writing culture. This method is the ‘Reconstruction (comparative) method that is applied to a number of languages which are known to be related, and of whose sub-classification are reasonably known.

“Reconstruction consists of examining systematically sets of words in the language under study which have similar meanings and enough similarity in form to suggest that they probably descend from the same word in the proto-language”. Such words have been referred to as look-alikes and must be proven whether or not they are cognates presently, that is that the words definitely were the same words in the proto-language or not in the past, and if so, to reconstruct the probable form of that word in the proto-language. Reconstruction rests essentially upon the principles that sound change is regular. That is, if a certain sound in a particular language [dzi] changes to a different sound [di] under certain conditions, that sound will change under the same conditions in all the other words in the language.

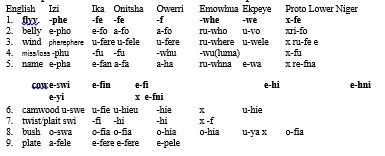

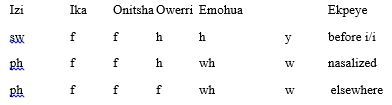

In Figure XX (below), ‘fly v’ differs only in its first con¬sonant in the various languages/dialects given. Izi shows ph- corresponding to f-in Ika, Onitsha and Owerri, to wh- in Emowhua, and to w- in Ekpeye. Comparing this set of sounds with those in words 2-4, we find that exactly the same consonants are found in each speech-form. Since the correspondence is found not just once but four times, we say there is a regular sound correspondence:

Izi ph = Ika f = Onitsha f = Owerri f = Emohua wh = Ekpeye w Coming to item 5, we find a difference: Owerri shows h-instead of f- as in 1-4. We therefore look for any condition, which are different from those for 1-4, and immediately observe nasalization is present in Ika (indi-cated by the final -n), in Owerri (indicated bya tilde), and in Emohua (indicated by -n-between consonant and vowel). We therefore suspect that the different reflex (result) in Owerri may be due to the presence of nasalization. This is confirmed by item 6 ‘cow’, which also shows nasalization in the same speech-forms, and again has lv in Owerri. Item 6, however, brings some new problems. Izi shows sw- instead of ph-, Emowhua shows h- instead of wh-, and Ekpeye shows y-instead of w-. These cannot be explained by the presence of nasa-lization, for they were not found in 5, which is nasalized. We therefore look for a different conditioning factor (condition which causes the difference), and observe that the vowel following the consonant here is i, which did not occur in the earlier items (they have e, o, u, and a). The same happens in item 7, which again has i, and items 8 and 9, which have i. Finally; we note that 7-9, although not nasalized, show h and not f in Owerri. Here the conditioning factor also seems to the vowel i/i. Thus, our formula for the regular sound correspondences now has to be more complex:

The next step (in Figure XXI) is the actual reconstruction that is to decide what the original sound was. It is not always possible to come to a final decision on this, but the type of reasoning applied is shown for this particular case. We can rule out fr as the original sound;/often changes to fr or wh, but not vice versa. Again, wh can easily change to w (as it has done for those English speakers who pronounce while the same as wile), but not vice versa. Similarly, f can easily change to fry before a close front vowel like i or i, and fry can then become y. f can easily become ph (voiceless bilabial fricative), especially before a back vowel. In fact, all of the sounds can develop easily from f except sw, and even here a little experimentation suggests it could perhaps have come from ph. Thus, we reconstruct f as the most likely proto-sound from which others developed. To show it is reconstruction and not actually a recorded sound, we prefix it with an asterisk or star: f.

Reconstructed proto-Lower Niger forms of the culture words in Figure XXI have been given in the last column. The complete words, like the single sounds, are asterisked to indicate that they are reconstructions and not attested (actually recorded) forms. Through reconstruction we thus determine the true cognates in a set of languages. This enables us to check again the judgments of cognation made in lexicostatistics. First, because of sound changes there may be some words, which are cognates but not look-alikes. For example, without having worked out sound correspondences one might doubt whether Ekpeye ‘uya’ was cognate with Izi ‘oswa’. However, because of their regular correspondence, they are cognates.

Secondly, some look-alikes may prove not to be cognates. An example is ‘(breakable) plate’, item 10 in Figure XX because of their similarity; they could be taken for cognates. By comparison with items 1-4, we see that f in Onitsha and Owerri should correspond to wh in Emohua and w in Ekpeye; instead we seefin Emohua and p in Ekpeye. This means that, although they are descended from the proto-Lower Niger, they are not cognates. Rather, the Emohua and Ekpeye forms are likely to have borrowed from Igbo or Ijo. This is because Ekpeye has nof, all cases of f in loanwords are changed to p. It is, in fact, very unlikely that proto- Lower Niger, which was probably spoken some two thousand years ago, should have a word for ‘breakable plate’, since this item of material culture was probably introduced from the time of European trade. It was perhaps introduced through Ijo, which has efere in many dialects, for example Epie in Yenegoa. When a standard list is completed for the languages being compared. Then for each item on the list, each pair of languages is compared and a judgment of ‘cognate’ (i.e related), ‘not cognate’, or ‘doubtful’ is made. An example is the comparison made in Figure XX. When all items on the list have been compared, the total of cognate items for each pair of languages/dialects is counted and worked out as a percentage following the formula:

Cognate/(Cognate+non-cognates) x 100

A percentage is then obtained for each pair of languages/dialects compared. These percentages can then be arranged in a tabular form. If the percentage is high it shows that the period of separation of speakers of the languages is recent, but if low shows a remote relation-ship but related. Having been involved in a marathon analysis of previously contiguous and presently non-contiguous languages and peoples; it has become necessary for the reappraisal of the historic affinities of particular West African peoples. This is as it concerned their points of origin, possible linguistic and cultural affinities; and the probable time that have elapsed since their separation and degree of divergence. The thesis would at this juncture consider some examples to prove that we have not all along embarked on a wild goose chase; and in the process attempt at proving probable relationship with the Igbo speakers.

English: Igbo Dialect: Lower Niger %Similarity

Language Abam Ndoni/Ekpeye % Disimilarity

one olu ofu +

two abuo abuo +

three ato ato +

four ano ano +

five ise ise +

I mu me +

You (thou) gi yu -

We anyi anyi +

You (ye) unu unu +

Head isi ishi +

Hair agbisi agirishi +

Eye anya anya +

Ear nchi nti +

Nose imi imi +

Mouth onu onu +

Tooth eze eze +

Tongue ire ire +

Neck olu onu +

Breast(s) era ara +

Heart mkpuruobi obi +

Belly avo afo +

Navel otubo otubo +

Hand aka aka +

(finger) nail mbo mbo +

Leg okpa ukwu/okpa +

Knee ikpere ikpere +

Skin akpukpo ahu asu +

Bone okpukpu okpukpu +

Blood ngbei obara -

Saliva onumini onummiri +

Fat abibia abuba +

Meat anu anu +

Horn mpi mpi +

Tail odu odu +

Feather abuba abuba +

Egg akwaa akwa +

Bird nnunnu nnunu +

Fowl okuko okuukwu +

Fish azu azu +

Dog nkita nkita +

Goat ewu ewu +

Housefly iji agizi +

Tree osisi osisi +

Seed mkpuru mkpuru +

Leaf akwukwo-osisi akwukwo-osisi +

Root mgborogwu mgborogwu +

Fire oku okwu +

Ashes ntu ntu +

Smoke anwuru-oku anwuru-oku +

Sand aja nbom -

Stone nkuma nkume +

Ground ali ani +

Road uzo ezuku +

Mountain ugwu ugwu +

Sun anwu anwu +

Moon onwa onwa +

Star kpakpando kpakpando +

Night abali uchichi -

Water mmini mmiri +

Person madu madu +

Man ikom onyeke -

Woman iyom onyenye -

Child nwanta nwanta +

Name afa afa +

Big ukuu ebu +

Small ntii ntikiri +

Long akaa ogonogo -

Red ufie-ufie ufie +

Black ojiri oji +

White ocha ocha +

Hot di-oku oku +

Cold oyi oyi +

Full juru-eju juni-eju +

New ohuru ofu +

Good di-nma di-nma +

Dry kporo-nku kponi-nku +

Eat ria ri +

Drink nua nu/ra +

Bite taa ta +

Swallow lua noru +

Roast mia suma -

Bathe hua wu +

Walk jea jea +

Jump fea wu +

Come bia bia +

Sit down duru-odi nodi-ani -

Lie down jinanga diari-ani -

Sleep ura/rahu rasu +

Give birth mua mu +

Die nwua nwusu +

Bury lia ni +

Say kpai kwu +

Kill gbua gbufu +

Steal zua zuru +

Give nye ye +

See fu fu +

Hear nu nu +

Know mara mari +

Blow ku gbe -

Figure XXII: REVISED MORRIS SWADESH 100 WORD LIST

Percentage:

Cognate/(Cognate+non-cognate) x 100/1

10/(10+90) x 100/1=1% (High %)

The comparison in Figure XXII shows that the Abam and Ndoni (where their oral traditions and those from contiguous communities recount they migrated from) share a high degree of similarity in their basic vocabulary and, therefore, highly suggests a separation of the communities in the recent past tentatively to about 1000 years ago. Therefore, the Igbo speakers who are of the Lower-Niger language division which belongs to the proto-Niger-Kordofanian phylum, can rightly be said to have migrated from the west of present day Nigeria, in the not too remote past, where they existed alongside the speakers of the Edoid division of the Eastern Kwa of the Eastern-Niger Congo. But an attempt at pinpointing the actual homeland of the Igbo places it at Ekpeye (see figure XII below). If we should follow the principle of point of origin of speakers of a particular language or groups of languages, it would appear the Lower Niger homeland would be around the area of Ekpeye in the south as a result of its distinctiveness from the other languageswhich show a language cluster sharing high degrees of linguistic and cultural affinity. This is even, further, substantiated by ethnography.

LOWER NIGER

EKPEYE IKWERRE OGBA IGBO UKWUANI IKA IZI EZAA IKWO MGBO

(Language Clusters since culture word similarities are high)

FIGURE XXIII: PINPOINTING IGBO HOMELAND

Summary and Conclusion

This chapter has painstakingly surveyed the possibilities of using linguistic data as a veritable tool for reconstructing past histories, especially the origins of motley acephalous African communities that have not been documented because there was no writing culture. Before now, historians depended on the scanty results of archaeology in their reconstructions; and in addition to the tendency to being selective in researches. Historians have been heard saying: this belongs to the linguist, anthropologist or sociologist, whereas, a well-conceived interdisciplinary research approach would be encompassing. Where archaeological excavations, analyses and interpretations have not been carried out, lexicostati sties comes in handy as tool since it goes further into the remote past. The thesis discerned and, in fact, portrayed the qualities of linguistics as fodder worthy of usage by the historian.

Definitely, linguistic data goes far back into the remote past than oral traditions, and as much as does archaeology. It is an invaluable source/fodder for historical reconstruction because the determination of the origin of a language is equally the determination of the origin of the people who speak it.

References

O. E. Uya, “Trends and Perspectives in African History” in E. O. Erim and O. E. Uya, Enugu: Fourth Dimension Publishing Company, 1984, p. 1.

Uya, p. 8.

Uya, pp. 8-9.

Robin Hallet, Africa to 1875, London: Heinemann Educational Books, 1970, p. 13.

J. O. Ijoma, “Igbo Origins and Migrations”, National Symposium on Igbo Origins and Culture, Benin City, May 21, 1983, p. 1; C. Wrigley, “Linguistic Clues to African History”, Journal of African History, Vol. 3,No. 2, 1962, p. 269; E. J. Alagoa, 1975, ‘The Interdisciplinary Approach to African History in Nigeria”, Presence Africaine, No. 94; Kay Williamson, “Principles and Techniques of Language Classification”, Paper presented at the 27 Annual Historical Congress, University of Port Harcourt, 13 - 17, April 1982.

Kay Williamson, 1962, “A Glottochronological Study of Six Niger-Congo Languages”, Unpublished Term Paper, Yale University.

Kay Williamson, “Principles and Techniques of Language Classification”, Paper presented at the 27 Annual Historical Congress, University of Port Harcourt, 13 - 17, April 1982.

Kay Williamson, “Linguistic Classification”, Unpublished Handout, School of Humanities, University of Port Harcourt, 1981.

Williamson.

Williamson.

Williamson.

Williamson, 1982.

Williamson, 1962.

Williamson, 1981.

Chidi Ejikeme Osuagwu and Charles Okeke Okoko, “Igbo Origins: A Linguistic Perspective to a Persistent Controversy”, www.osuagwu/okoko/igboorigins.

J. H. Greenberg, “Classification of African Languages”, 1963; J. H. Greenberg, Languages of Africa, Bloomington, 1966, pp. 7 - 15.

Eastern Niger-Con go is a term that was proposed by J. T. Bendor-Samuel as simpler than Bennett and Sterk’s 1977 ‘Eastern South-Central Niger-Congo’. In Greenberg’s classification, it was the equivalent to Eastern Kwa (minus Ijo- Defaka) plus Benue-Congo.

Robin Horton, “The Niger-Kordofanian Diaspora: Another Aquatic Saga?” Paper at the 27 Annual Congress of the Historical Society of Nigeria, University of Port Harcourt, 13 - 17 April 1982.

Lower Niger is a term introduced by Kay Williamson in 1973.

O. U. Kalu, “The Battle of Gods: Christianization of the Cross River Igboland, 1903 -1950”, Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria, Vol. 10, No.l, December, 1979, p.l.

Williamson.

Williamson.

Williamson.

Williamson.

Williamson.

Williamson.

Kay Williamson, “History Through Linguistics”, Journal of African History, Ibadan, Vol. 17, 1963.